An Open Letter to Laguna Blanca School

June 6, 2020

Published on edhat santa barbara

My name is Karinna M. Carrillo and I went to Laguna Blanca School for thirteen years. A private school nestled in Hope Ranch and Montecito– two of the most lavish neighborhoods in Santa Barbara, California. Montecito and Hope Ranch, where the average property value is estimated at over $2 million.

My dad was the school’s janitor. I grew up knowing that he was coming home from work late, tired, and probably sad. He stayed working there because he wanted to give his kids an education that would endow them with an opportunity for better than what he had. At the time, Laguna provided its workers with the opportunity for tuition remission for their children. This is how my sister, brother, and I were able to attend the school with an average annual tuition higher than California’s own public universities. My siblings and I probably made up half the school’s then “diversity”. There was also my cousin, and three Black students; that was it for the school of under 400. We were the financial aid kids, the not-white kids, and the janitor’s kids; I knew this from as young as I can remember.

Unlike the public schools in our district, at Laguna, we had to pay for everything–our books, our lunch, and our very expensive, navy blue, white, and red uniforms. I recall my classmates arriving with the brightest white button downs and being envious of the girls who were lucky enough to own trousers, skorts, and dresses. My siblings and I typically had what Sears had in stock. We arrived to campus with the best our family could afford. Soon enough though, I remember receiving a letter that we should be certain to only wear clothing that included our school’s emblem and were from Lands’ End’s magazine. They didn’t ask if we were OK or needed support. That was the beginning.

Before owning a home computer, my sister and I used the ones in the faculty room while my dad worked. Again, my family received a letter asking all workers to stop bringing children to work to use school computers. There was no personal inquiry regarding your students’ wellbeing or ability to access resources. No inquiry regarding your staff’s ability to provide childcare. Laguna didn’t see race, they didn’t see class. They never asked. Almost as if mentioning the words would imply offense. “Community,” they proclaimed, but “unity” there never was.

By sophomore year, I was well aware of class differences between my classmates and me. The problem was that my sister and I went to school with some of the country’s 1%, and Laguna did nothing to support the students who weren’t. Students whose parents were surgeons and CEOs; students whose parents never worked, but were wealthier than I ever knew. We went to school with families who owned islands, lived near Oprah, inherited chewing gum companies–that type of generational wealth that isn’t seen with Black, Indigenous, or People of Color because systemically, it wasn’t meant for us.

My sophomore year, hiring private college counselors was all that anyone was talking about. Meanwhile, I was just learning what the SAT was. I was a first generation student, but Laguna didn’t see these differences, and they definitely didn’t act to instill any sense of equity on campus. So I missed class trips and went without certain textbooks because of financial barriers. My dad worked side jobs for a Laguna teacher and in exchange she agreed to review my college essays. To my surprise, however, when my parents and I visited Laguna’s college counselor, he advised that due to our likely need of financial aid, I should probably just consider attending the city college. He did not once refer to programs for minority students, advise on any scholarships, or acknowledge my academic excellence. To him, and by extension, Laguna Blanca, I was different and didn’t measure up to the students whose parents paid for the school gala or new gymnasium. To him and Laguna Blanca, I wasn’t worth their time. That same year they took away staff tuition benefits. White faculty only.

I went on to graduate from the University of Southern California with a merit scholarship and currently attend Columbia University with a merit scholarship for my academic achievement and leadership in public health. Everyday, I work to advance the health and wellbeing of low-income communities and communities of color and know now just how valuable the experiences during the formative years of a child are.

Laguna Blanca School is not built to support students of color, marginalized students, students from working families, or immigrant students. It exists to support the wealthy, privileged, and white.

You’ve posted the black square. You’ve proclaimed student diversity. As a student who represents a likely very high percentage of your school’s historical diversity, hear my demands:

1. Hire Black, Indigenous, and POC (BIPOC) educators. I did not have one Black teacher. I grew up never seeing a teacher who looked like me nor my parents let alone one who acknowledged my ethnicity. Hire them and not just as your custodial staff. Hire BIPOC and give them positions of leadership. Put them on your board, make them your president.

2. Establish a Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Taskforce. This taskforce should exist to ensure the success and safety of BIPOC students, faculty, and staff.

3. Create a Diversity, Equity and Inclusion Officer. Add this officer to your board of trustees who exist to ensure the school is accomplishing its mission and upholding its core values of scholarship, character, balance, and community. The current board of trustees serves as counsel and guidance, however, the positions are filled by some of the most wealthy parents and alumni.

4. Commit to the advancement and success of your BIPOC and low-income students. Hire staff who are invested in supporting students of color. Ensure your BIPOC students have all of the resources they need to succeed.

5. Facilitate discussions and create space for your BIPOC students, staff, faculty, and allies. Racism is real; classism is real; xenophobia is real. Not discussing it does not make it go away. Talk about the issues our world is grappling with. Host community conversations and education surrounding how to be an ally.

6. Create a community advisory board for the Hope Ranch Patrol. The advisory board should review racial and identity profiling, partnerships with the larger Santa Barbara Police Department (SBPD), officer training, and disciplinary matters. This advisory board should release significant findings and advancements to the school community.

7. Acknowledge your own Anti-Blackness. The only way forward is for all to recognize the role we’ve played in White Supremacy. Laguna Blanca School must recognize how it, as an institution, is deeply intertwined was created to support white people and not communities of color, but will work to dismantle our racist past.

8. Pledge to financial responsibility. The school should commit to financial donations to organizations like Black Lives Matter and additional resources for its BIPOC and low-income students.

Sincerely,

Karinna M. Carrillo

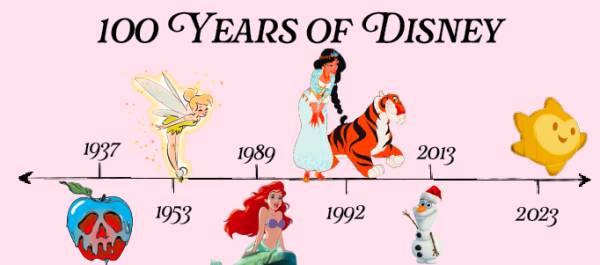

Laguna Blanca School Class of 2013