The Holy Days Behind the Holidays

As our culture changes, religious holidays morph into secular versions of what they were originally intended to be.

February 26, 2020

Over the past couple of months, we have managed to give and receive all of our wishes of “Happy Holidays,” “Merry Christmas” and “Happy Hanukkah.” Whispers of Easter are on the horizon, but many of us frequently forget where these contemporary celebrations originate.

Rather than traditionally celebrating religious holidays, some celebrate Christmas in a modern, all-American version of those old observances.

Many Christmases are about getting presents out from underneath the Christmas tree, with large dinners and as much of the family as can fit around the table, as everyone enjoys the new holiday Spotify playlists.

Leading up to the Christmas holiday, people sing, celebrate, and enjoy a long dose of relaxation.

Once the holiday is over, people pack up the ornaments, retrieve the star from the top of the tree and get ready for New Year’s Eve celebrations.

When Easter comes around, however, it’s an entirely different story.

Children get a kick out of finding Easter eggs hidden around the yard. But, once they get to high school, it’s not much of a stretch to say that many typically forget the holiday altogether.

But their celebrations probably don’t need further discussion: they’re well-known and well-observed.

What many don’t know all that much about, however, are the ancient Holy Days on which our modern holidays are founded.

To find a greater appreciation for festivities, then, it is necessary to learn a little of the traditions in which they are grounded. Christmas is among the oldest Holy Days established by the single oldest existent Christian Church on earth: the Roman Catholic Church.

References to the Holy Day go as far back as 204 AD under Pope Saint Zephyrinus, and the devotions and traditions associated with Advent only grew going forward.

Advent, the Christian liturgical season leading up to and culminating in Christmas, is traditionally held as a season of hope, expectation, and preparation for the eventual celebration of the Nativity of Christ on December 25.

In stark contrast with more secular Christmas traditions, it is not a period of partying and gift-giving, instead it focuses on prayer and the contemplation of holy things.

The entire season is meant to bring the Christian’s soul closer to, and more ordered with, God.

Christmas Day itself is the second most important holy day in the entire Christian religion.

It has been celebrated on the same date according to the traditions of the Catholic Church by every major Christian denomination in the history of the world, and has historically been celebrated with a special form of the Mass in the Catholic and Orthodox Churches, accompanied by feasting, singing, and celebration which continues on for another 12 days, culminating on the Feast of the Epiphany, the day on which the Three Wise Men are said to have visited the infant Jesus in his manger.

Ironically, Easter, the holiday which many forget or skip straight over, is the single most important day of each year by Christian reckoning.

Celebrating the Resurrection of Christ, it stands to commemorate the ultimate triumph of God over all things, even death.

The day is also one of feasting and celebration, traditionally accompanied by three-to-five hour church services and baptisms.

The Holy Day is made all the more important by the simple fact that it follows the 40-day liturgical season of Lent, which is held by a majority of practicing Christians to be a time for fasting and abstinence.

The lack of decadence during this preparatory Lenten period, when juxtaposed with the euphoria of the Easter holiday and the Easter season following it, puts the passing of time in a very different light for those who observe the liturgical traditions of Christianity.

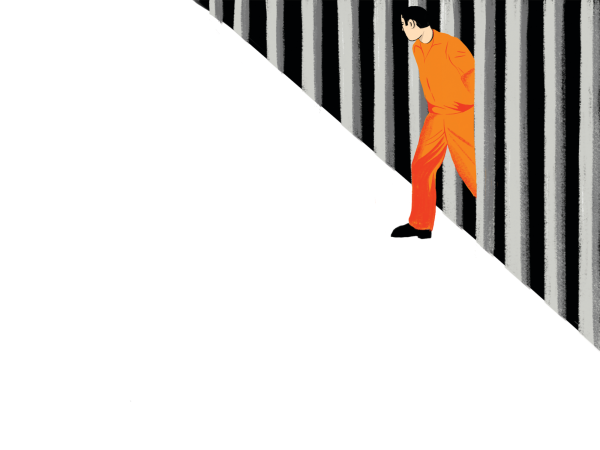

The observance of these seasons and celebrations, however, comes at considerable risk for the millions of Christians who live in nations that have a policy of persecution and extermination against Catholics and Protestants.

In places like The People’s Republic of China, practicing of the traditional Christian faith is entirely illegal, and anyone observing the old rites and liturgical seasons is immediately picked out by their government for further surveillance and possible imprisonment and torture.

For Chinese Christians, not even the genuine threat of death can keep them from the observance of their Holy Days.

The vast difference between secular holidays and Christian Holy Days, then, is that while many see these holidays as convenient breaks from the real world, breaks which are if need be, expendable, the Christians hold their Holy Days to be essential parts of life. Specific days and certain times mean certain things.

Days and their meanings are inseparable from one another, and it is outside of the control of humans and human institutions to alter them.

Christian celebrations behind the seasons on the calendar are very different from those two days, which have been set aside for some time off of school or work.

In the secular tradition on which our society is constructed, Monday through Friday is set aside for school or work, and Saturday and Sunday are (in theory) time with which people can do with what they will with the weekend.

For the traditional Christians, different dates, different days of the week, and different months and seasons mean different things.

Almost every day is set aside for something unique and something out-of-the-ordinary. They perceive the passing of time fundamentally different than others.

“Traditions represent a critical piece of our culture. They help form the structure and foundation of our families and our society. They remind us that we are part of a history that defines our past, shapes who we are today and who we are likely to become. Once we ignore the meaning of our traditions, we’re in danger of damaging the underpinning of our identity,” said Frank Sonnenberg in “The True Meaning of Holidays.”