DRIED OUT, THEN DRENCHED

Santa Barbara starts off the new year by transitioning from drought to “bomb cyclones” that remind residents of the 2018 mudslides and hint at the future of climate change-fueled weather.

April 10, 2023

For years, Californians have fretted about too little rain while suffering regular wildfires and continuous droughts. A healthy amount of rain was said to be just what California needed. What California didn’t expect, however, was for these wishes to manifest into a “bomb” cyclone, which devastated the West Coast with extreme flooding, extensive damage, and even deaths.

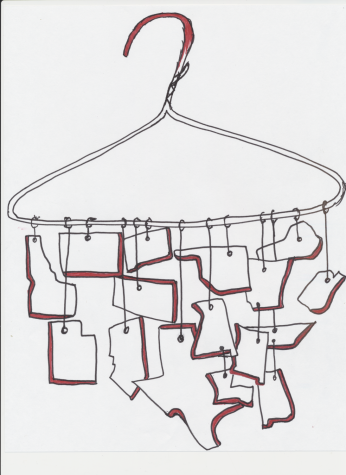

Santa Barbara, along the coast of California, was in the thick of the events. All 15 zones of Montecito, as well as other parts of Santa Barbara county, received mandatory evacuation notices. The National Weather service predicted 4-10 inches of rainfall in the mountains, and 2-5 inches of rainfall in urban areas.

Amidst the waves of storms hitting the coast, the California Highway Patrol closed highways and major roads in Santa Barbara and San Luis Obispo counties. Parts of Highway 101 and Highway 154 were closed, including many other popular cross-streets. Hundreds of cars were left on the roads, not able to get out of the traffic due to creeks flooding the freeways.

“Most of the year, there is no water,” Blake Dorfman, Dean of Students, said, referring to Sycamore Creek that runs in front of his yard. “The creek basin is about 15 feet deep. When I arrived home after evacuating the school, I was shocked to see that the basin was entirely filled with rushing water.”

The damage and panic pushed the city’s public services–fire, police, and public works departments–to scramble to mitigate the damage. Thankfully, the county can be happy to say that there were no deaths or injuries reported from hundreds of rescues, and no homes or buildings were damaged beyond repair.

Flash floods and sand bags are not unfamiliar to Santa Barbara residents. Some of the heavy rains back in January coexisted with the anniversary of the 2018 Montecito mudslide, a series of mudflows that devastated the homes and lives of the community.

The permanent damage of lost lives and flattened homes was a disheartening memory during the recent storms. The rains hit the county on a physical and emotional level. Nevertheless, after years of recovery, the public started preparing for future natural disasters by introducing flood warning systems, constructing dams, and strengthening community ties.

While the heavy storming ended back in January, the cautionary messages from the damages still last. This natural disaster is what is called a “bomb cyclone,” a monstrous, rapidly intensifying storm associated with a sudden and significant drop in atmospheric pressure that came from over the Pacific Ocean. These waves of weather are super-fueled with tropical moisture from a potent atmospheric river, which is essentially a conveyor belt of concentrated moisture in the atmosphere emerging from the warm waters of the Pacific Ocean. Approximately 9 of these atmospheric rivers hammered California in a 3 week period.

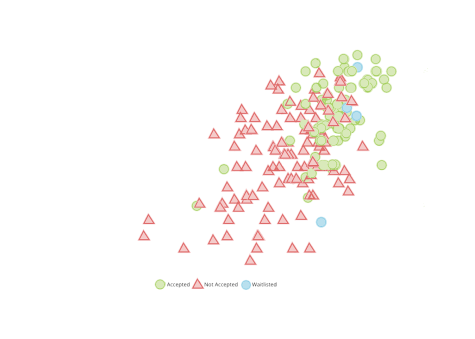

The rain has proved to be yet another effect of climate change. On a statewide basis, approximately 11 inches of rainfall materialized. 700 landslides, power outages affecting more than 500,000 people, and levee breaches sprawled throughout the state. An estimate of over $1 billion in damages and up to 22 deaths were blamed on the weather.

According to Yale Climate Connections, the storm damages were a preview of what a true California megaflood will wreak. The golden state has suffered a long history of cataclysmic floods and heavy droughts, and both can be directly connected to climate change. This dramatic shift in the weather and intensification of California storms is another warning that mother nature is not happy.

This isn’t the first time California faced warnings from the weather. Climate change-fueled megadroughts have contributed to the damages by draining the state’s reservoirs and triggering water shortages.

“Rising summer temperatures make the soil and vegetation drier, increasing the chance of drought and wildfires,” says climate scientist Shradda Dhungel, of the Environmental Defense Fund. “Then in the winter, when California gets most of its precipitation, warmer air with massive amounts of moisture unleashes these big storms that are wetter and more intense. Because of these two sets of conditions, it’s possible to have more intense droughts and more intense storms and flooding.”

As weather gets more and more extreme, it’s important to trust the experts in the science community who are pointing to climate change being the culprit. If global warming continues to rise, California– along with the rest of the world– will have to face much more than a few weeks worth of flooding.