In a Housing Funk

Santa Barbarans clash over a development project in the Funk Zone.

April 9, 2023

When 155 new housing units were proposed in the busy downtown Funk Zone, it should have been cause for celebration, but instead, there was vitriol.The SOMOfunk development, led by developer Neil Dipaola, would be built on a 2.1 acre block in the Funk Zone, and would include 29 affordable units and 18,000 square feet of commercial space. The existing structures on the block would be demolished, causing anger in the community. Despite Santa Barbara’s lack of affordable housing, residents lined up to oppose the project.

Opponents believe the development will alter the “character” of the Funk Zone with dense housing, a large building, and a disruption of views. KeeptheFunkSB, a newly incorporated non-profit, is organizing Funk Zone businesses and residents against the plan. On their website, they claim that the development will “devour the existing neighborhood and change it forever” due to blocking “important public views” and displacing some areas for the fishing industry and “artist studios.”

“We’re not against housing,” says KeeptheFunkSB on Instagram. While the organization claims the “rest of the neighborhood will suffer as a result” of the development.

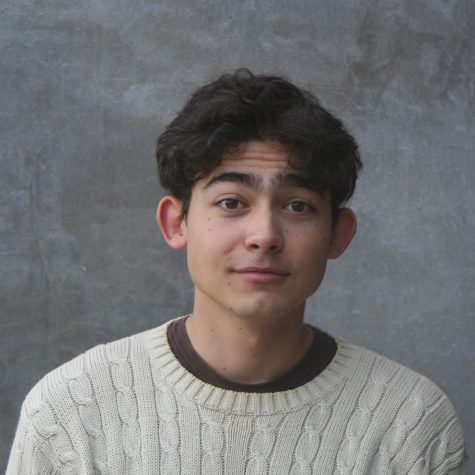

“Building more housing is a no brainer,” said George Nicks ‘22, who is passionate about this issue.

“Housing prices have shot through the roof, and unless we build more they won’t go back down. NIMBYs can complain all they want about character, but I personally feel that reducing homelessness, increasing walkability and lowering rents (while increasing property values) so people aren’t priced out of their homes does more to preserve character than stopping new construction ever will.”

Keep the Funk supporters claim to oppose “gentrification”, but supporters of the project say that when housing isn’t built in sought-out affluent neighborhoods (like the Funk Zone), people moving into the city rent or buy in working-class neighborhoods. They claim that if housing was built in the Funk Zone, it would bring rents down and reduce the pressures of gentrification.

On the one hand, opponents to the project can point to the Funk Zone’s parking problems as evidence that the added density will strain the infrastructure of the neighborhood. That’s wrong, according to George. “More density reduces car dependency, by making walking and public transport more convenient, and reducing the need for wasteful street parking,” he says.

The battle over SOMOfunk serves as a microcosm of a growing political debate across California. The state has big goals for housing and has required counties and municipalities to open up areas for growth in order to meet their RHNA (Regional Housing Needs Allocation), the predicted number of new homes over the next decade.

In the quest to get those units zoned, policymakers are coming into conflict with residents who’d rather “pass the buck” on where new housing is built than accept change to their community. Although the policy consensus is moving towards a “YIMBY” (Yes in my backyard) rather than “NIMBY” (Not in my backyard) approach to housing, local politics is dominated by homeowners, who are more likely to oppose new construction, especially apartments.

No matter the result of the application process for SOMOfunk, Santa Barbara needs to build more housing. ile our city’s policymakers are generally united in support of increasing affordable housing, it becomes a much more divisive issue when we have to figure out where to put it.