The Perils of Redistricting

Redistricting throws the political balance of power into question as commissions and politicians redraw the lines.

March 2, 2022

At the beginning of each decade, the slow moving levers of our democracy begin to chug steadily along.

The U.S. Census (a Goliath survey sent to every American household), concludes, and the Census Bureau releases the congressional apportionment, the process of dividing the 435 seats of the House of Representatives proportionally.

Then, states individually begin the process of redistricting, the procedure of drawing district maps. Redistricting is an extremely politically-charged task.

Gerrymandering, the process in which political parties or politicians manipulate district lines in order to favor themselves, is common. It’s effective because it reduces the amount of competitive districts and protects incumbents from the threat of losing re-election.

Gerrymandering “is a destruction of our democracy,” said Social Science Chair Kevin Shertzer. “It’s a corruption of the people’s voice, and it’s those in power using the system to stay in power.”

According to Shertzer, since gerrymandering impacts the legislative branch, it impacts the rest of the government, and the entire country because the legislature is supposed to balance out the rest of the branches, and has the power to enact laws that impact all of us.

Upsetting the constitutional balance has massive repercussions across our democracy, allowing parties and politicians to neglect their duties for reasons of self interest.

After the census webcast concludes, tens of thousands of redistricting analysts and political operatives scramble to begin analyzing the results of the census and start to plan to draw district maps for the next decade.

In states like California, Colorado, and Washington, cities, counties, and state governments begin the long selection and approval process for choosing members to draw their maps.

In other states, like North Carolina, Texas, and Illinois, politicians rush to meet with consultants, operatives, and political parties to draft maps from behind the scenes.

The process is both sluggish and rushed: maps must be finalize mere months before the first primaries of the next midterm elections, and every stakeholder from congressional incumbents to minority advocacy groups must wage an all-out effort to create the most advantageous plan that will be set in stone for the next decade of political battles.

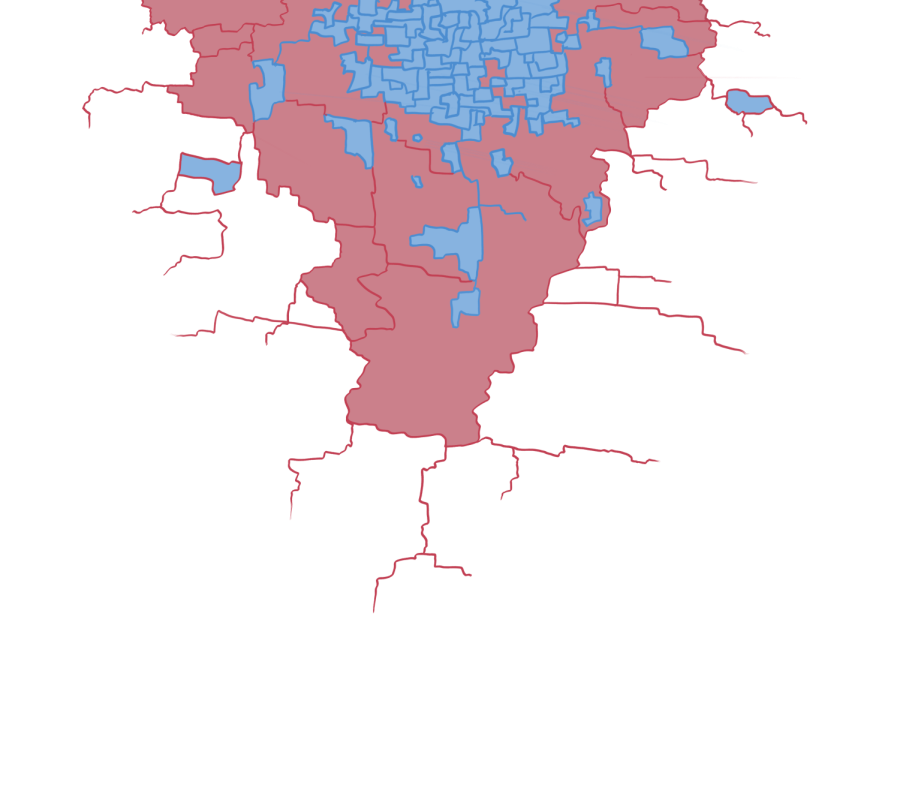

California’s statewide independent redistricting commission released a draft congressional map on Nov. 10.

While Santa Barbara’s district is relatively unchanged from before, spanning San Luis Obispo to Ojai, the rest of the state has experienced major changes. In 2018, Santa Barbara voters approved a measure to appoint 11 independent citizens to form a redistricting commission for the Board of Supervisors map so that redistricting could stay independent of political and special interests, in addition to allowing for an increase in public input and transparency.

“The independent aspect is that we’re not paid by the county, we don’t work for the county, we don’t have an affiliation with them, we don’t work for political parties, we’re just ordinary people who are looking to do something good for our community,”said Megan Turley, Vice Chair of the Commission.

When creating a map, commissioners are required to take into account several factors, race and the Voting Rights Act, individual communities of interest, contiguity, compactness, cohesiveness, topography, and geography.

“We cannot be racially gerrymandering our districts within the county…our [legal] expert did determine that there is racially polarized voting, specifically in north county in this case. A lot of the Latinx community there does regularly vote together as a group for similar candidates, who white and other racial identities do not vote for,” Turley said. “So it would be illegal for us to not draw at least one district where they are the majority of voters.”

Commissions have to take into account a myriad of concerns and voices, and not all of them can get what they want. In the case of Santa Barbara, our commission has to make several tough choices.

“Santa Ynez Valley has expressed a lot of different opinions about being grouped historically with Isla Vista, and Santa Ynez valley on its own has about 20,000 residents,” Turley said. “So it can’t create a district on its own, it has to be grouped with either other like minded communities of interest or a different community of interest… it’s a huge balancing act, and obviously people have very strong opinions on it.”

On Dec. 8, the commission adopted a final map, which includes Isla Vista in the second Santa Barbara-based seat, concluding the redistricting process.