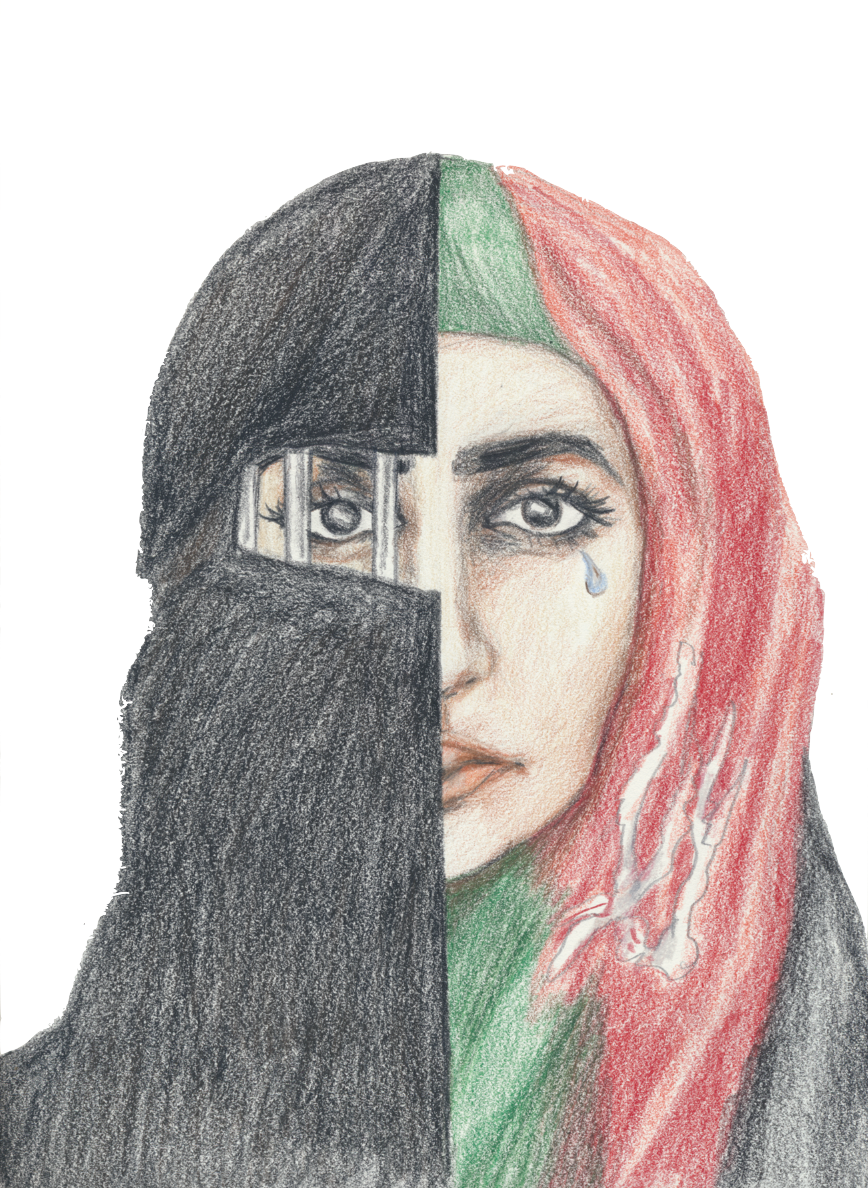

The angst, the display of restlessness—it was almost overwhelming. But, I was fascinated.

To me, this was art. It was graphic and alarming, powerfully dramatic, but, at the same time, pedestrian, and the fact that it all made me uncomfortable convinced me of its artistry.

I walked through Los Angeles’ MOCA Street Art exhibit entranced by the installations, the photographs, and the graffiti.

The exhibit’s common thread suggested a generational difference.

I walked through the exhibit with my grandparents. My grandma and grandpa are experienced art seekers.

As early as I can remember, my grandparents were the ones to convince me to try new foods, to teach me about different cultures, to tell me their worldly stories.

As a somewhat reluctant 12 year old, my grandparents dragged me to my first contemporary art museum, teaching me to recognize the genius of Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein.

But this—the murals of graffitied train cars, the painted cars, instillations of defaced property—was a different sort of contemporary “art.”

As much as my grandparents tried to appreciate the “street art” that I found to be so clairvoyant, I could sense that they were caught off guard.

Whether it was the exhibit itself or the colorful audience it drew, I knew they felt a discomfort that, unlike me, they didn’t tribute to the allure of the exhibit.

If someone takes a picture of the profanity graffitied across a bridge, can it become a powerful critique of societal corruption?

Is this idea unique to the tattooed and pierced?

Is it unique to a younger generation?

Or to a generation that pushes limits?

But, hasn’t teenage angst always fostered a breaching of boundaries to express freedom of speech and to display frustration?

Is our generation any different? The Street Art exhibit was extreme, but it was perceptive.

Art is subjective. Subjectivity is defined by experience not by fact, and street art has the capacity to dauntlessly portray experience.