Vibrant, upbeat K-Pop songs, such as “Butter” by BTS and “The Feels” by Twice, flood American radio stations. “Squid Game,” popular on Netflix, won six Emmy awards in 2022.

This reflects the Korean Wave, or Hallyu: the Chinese term for this global phenomenon to describe the influx of South Korean culture globally.

Although the Korean “flame” is popular due to a variety of characteristics—such as heart-wrenching K-dramas, the infamous Korean convenience store meals and drinks, and revolutionary cosmetics—what brought Hallyu to its global prominence is Korean pop, commonly referred to as K-Pop.

In the 1990s, the emergence of Seo Taiji and Boys paved the way for the contemporary K-Pop blending of both American hip-hop and rap beats. By the early 2000s, Hallyu and the Korean music industry peaked on the internet and social media.

Wonder Girls, a four-member girl group, was one of the first and most famous groups, referred to as the “first generation.” They accumulated over one billion views on YouTube with hits such as “Tell Me” in 2008 and “Nobody” in 2009.

Quickly following Wonder Girl’s success was PSY, who released the worldwide smash “Gangnam Style.” This song accumulated over 4.8 billion views on YouTube, crowned Song of the Year by South Korea’s music association.

Although there are many different groups contributing to the steady growth of K-Pop during the late 2010s, notable mentions are Blackpink and Twice. Blackpink, another four-member girl group, broke the charts with their debut song “Whistle,” ranking first on every major Korean music chart in 2016. Following this success, they released “DDU-DU DDU-DU” in 2018. The music video became the most-viewed video by a K-pop group on YouTube. Blackpink’s success popularized the “girl crush” concept, which embraces fearless femininity and female empowerment.

When the global pandemic struck, the continuous rise of various social media platforms surged dramatically; K-Pop had to adapt by placing more emphasis on digital platforms and social media. Virtual performances, live streams, and behind-the-scenes content became prevalent as a means to stay connected with eager fans. Although the pandemic hindered K-Pop as they could one, not connect to fans in person, and two, were unable to advertise traditionally—BTS, otherwise known as Bangtan Boys produced “Dynamite” which gained over 100 million views on YouTube in only 24 hours.

It also reached No. 1 on the Hot 100 chart in September 2020, becoming the first song by any K-pop group to reach the summit on the charts. The sudden increase of K-Pop fans joining on social media platforms–such as Twitter—increased fandoms and fandom culture, a phenomenon where fans select a particular celebrity or genre, uniting to cultivate a distinctive culture centered around mutual liking.

Fandom culture is a staple of K-Pop—calling themselves “stans:” a combined term for both “stalker,” and “fan.” “A lot of the culture around K-Pop is very fan-oriented in a way that it isn’t in the West,” Zola Peltz ‘23 said.

The K-Pop stan culture is becoming increasingly toxic with the rise of social media—although there are many music fandoms that have stan culture, K-Pop fandoms are extremist.

Fandoms are unable to accept criticism of their idols due to the culture of worship which is supported by K-Pop’s overall advertising; companies advertise their idols as almost god-like individuals, sparking a level of admiration so that fans will become obsessed and spend money on their group.

K-Pop companies advertise their idols in a manner that will form a para-social relationship with their idol. This strategy was adopted during the pandemic to make fans still feel engaged and connected.

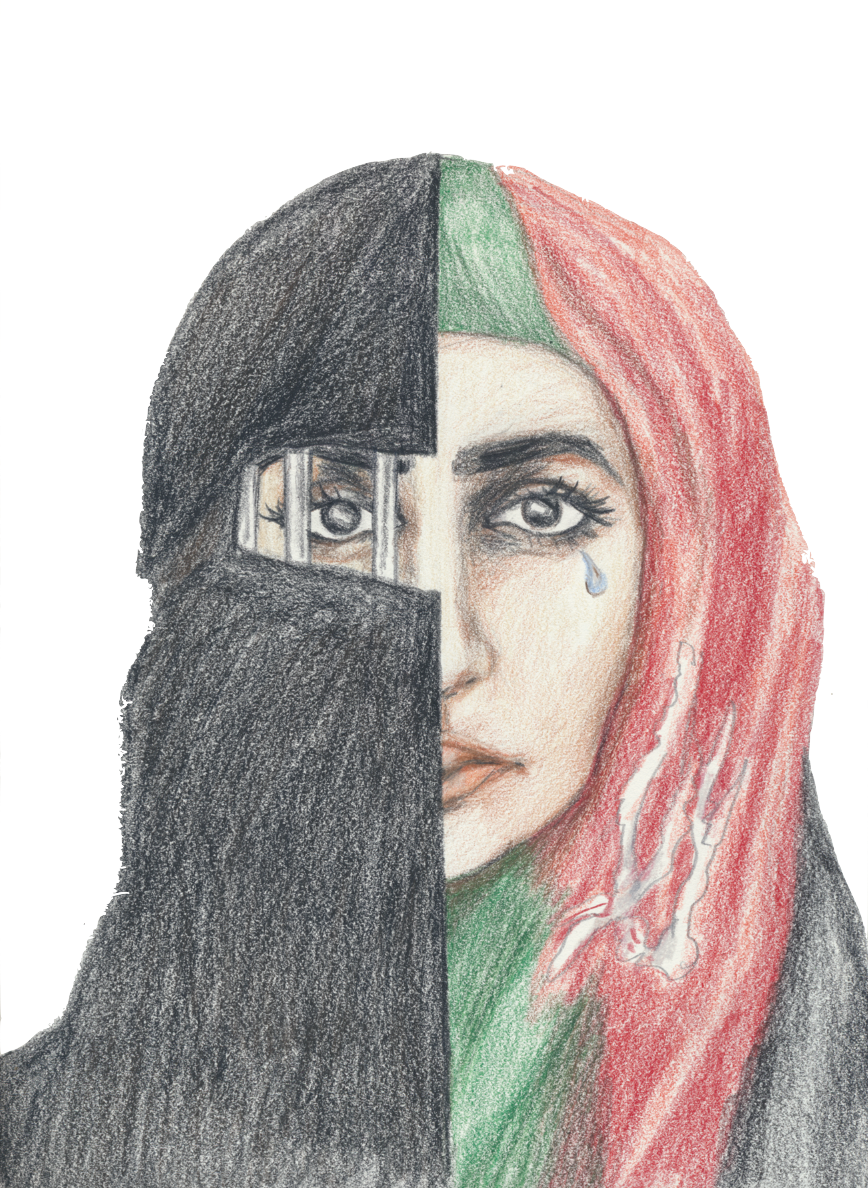

As toxic fan culture may be, artists engage in the toxicity as they must portray many unattainable beauty standards, causing a detrimental effect not only on the fans but also on the K-Pop artists themselves.

K-Pop is reflective of the Asian beauty standard: extremely thin figures and strict proportions. Companies expect their idols to have a 9-1 ratio where the body is nine times as long as the head, which is almost not physically attainable. Those who do fit into these beauty standards face multiple death threats for simply eating more “cutely.”

Jang Won-young is an example of this. Deemed the “Korean It Girl,” she is idolized to an extreme. In Won-young’s case, fans created a cult-like following named “Wonyoungism” where fans learn to achieve her body type and look like her.

K-Pop companies often impose contradictory views on their clients. Often, K-Pop idols have no choice but to commend these unrealistic standards in order to satisfy the companies.

Over the last few years, many K-Pop idols have gone rogue from these strict companies and gone out on their own. Most notably is Hwasa, whose lyrics are often about the problems in the K-Pop industry, such as the strict beauty standards. Another K-Pop sensation breaking free from the standard is (G) I-DLE, who recently wrote a song titled “Queencard,” which focuses on the protagonist accepting her appearance and realizing true beauty comes from self-confidence.

Although K-Pop has made tremendous progress in shifting and readjusting not only the beauty standards, but also the toxic fan culture, there is still much to be done in order to make K-Pop a less toxic music culture.

“With any fandom the bigger it gets the more toxic fans you get. This is why a lot of the most toxic fandoms are the biggest ones. Anyone who’s been online knows, the rudest people are always the loudest.” Zola said.