Prometheus stole fire from the gods and gave it to men. For this, he was chained to a rock and tortured for eternity.”

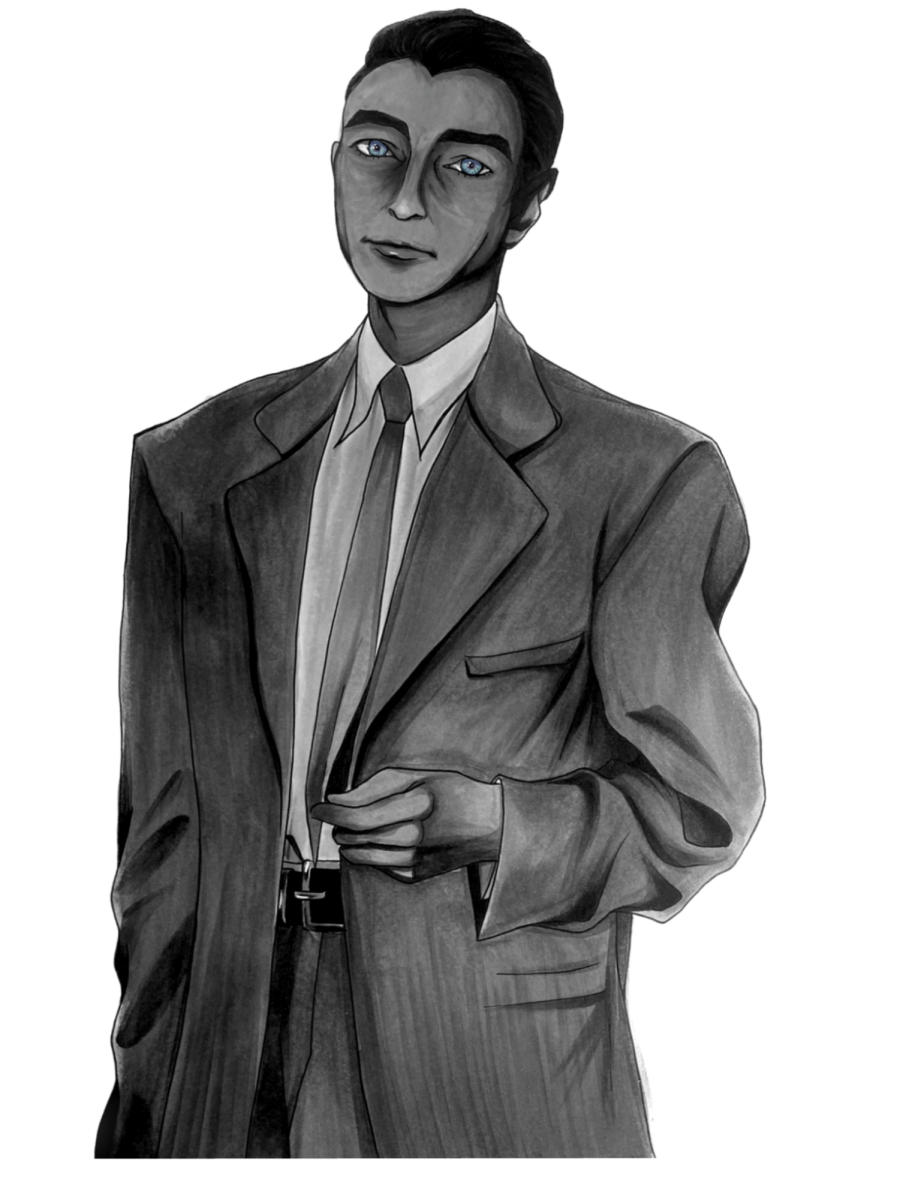

“Oppenheimer,” directed by Christopher Nolan and based on Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin’s biography “American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer,” premiered this summer, captivating audiences worldwide and grossing over $930 million.

In the film, Nolan compared J. Robert Oppenheimer, the father of the atomic bomb, to Prometheus, the fabled Greek antihero, for giving humans a source of power they never meant to have.

The film tells the life story of the physicist: his brilliance, complex romantic life, politics, and tortured conscience.

The three-hour feature film invites people to question the ethical repercussions of one of the world’s most powerful scientific discoveries and the danger Oppenheimer’s creation poses nearly 80 years later.

The film boasts an impressive cast of superstars, including Matt Damon, Emily Blunt, Robert Downey Jr., Florence Pugh, and Cillian Murphy in the title role.

“Cillian Murphy gave a great performance. He should get the Oscar for the movie,” junior Carson Stewart said. “Personally I couldn’t see anybody else getting it.”

Nolan’s creative choices — including unique use of color grading, delayed sound, intentional lengthy silence, and unnerving musicality — brought to life the internal and external trials Oppenheimer faced before, during, and after the use of his world-changing creation.

The film intercuts between two defining periods in Oppenheimer’s life. Nolan used coloring to distinguish between the running plots, and Oppenheimer’s young adult life through the use of his bomb in full color, contrasting the heavily biased investigation for his political stance in black-and-white.

The film did not glorify Oppenheimer’s achievement; rather, the early part of the film highlighted his limits as a physicist and a human being, prone to errors; he was clumsy in physics labs, attempted to poison his professor, and cheated on his wife.

“[The movie] really touched on every possible aspect and all the niche details of his life,” Carson said.

Oppenheimer himself is a paradox with contradictions; he is tormented by the eagerness for peace and the cruel means to achieve it. As the director of the Manhattan Project and the Los Alamos Laboratory, Oppenheimer held himself most responsible for the creation of the atomic bomb and struggled to live with the moral burden of creating the most destructive weapon the world had ever seen.

“No other country has ever used [atomic bombs], at least on cities or people. What a horrific decision,” Social Science Chair Kevin Shertzer said. Oppenheimer, alongside with other scientists and politicians, insisted on using the weapon on a city instead of dropping it on the ocean, believing that the world would only understand its power after experiencing it, hoping that this would not only bring an end to World War II, but all future wars.

“We want it to be so destructive so they won’t ever do this again,” Shertzer said.

The film reached its climax during the Trinity Test, the first detonation of the nuclear weapon, named after the Holy Sonnets by John Donne, ‘Batter my heart, three person’d God.’

An ominous mushroom cloud rose to the sky, bright as a thousand radiant suns, blindingly white, rolling out as it grew larger. It seemed to hang in the sky forever.

The sound reached people’s ears moments after: a deafening roar that rumbled and echoed through the mountains.

The bomb worked, and the world was changed forever, having unleashed an unprecedented method of destruction. Oppenheimer watched the explosion as he murmured to himself,

“Now I am become death, the destroyer of worlds,” quoting from the Hindu scripture, “The Bhagavad Gita” to describe his own doing.

Oppenheimer firmly believed in the necessity of using the weapon. However, it’s also clear that the guilt afterwards frightened him and completely consumed him, as evidenced in him telling Truman: “Mr. President, I feel I have blood on my hands.”

Unimpressed and annoyed, Truman called Oppenheimer a “crybaby.”

One key point of the film was to highlight the ignorance and apathy the general public — in Oppenheimer’s time and today — holds towards the use of nuclear weapons.

“People have no idea what nuclear energy is,” Shertzer said. “They have no idea. And that belief is pervasive.”

The film showed Oppenheimer’s “victory” speech to a cheering crowd of Americans, desensitized to the tens of thousands of lives the bomb had immediately taken; the deafening roar they made is no less powerful than the Trinity Test itself.

Oppenheimer himself seemed to understand the gravity of his creation and the devastation it caused and therefore refused to help the U.S. government with subsequent nuclear projects.

For refusing to contribute to the new projects, the government targeted Oppenheimer, launching a private hearing into his previous political ties to communism to cover his anti-nuclear views.

“He was unbelievably famous. So for him to be going against nuclear energy would not bode well for what they wanted to do,” Shertzer said. “So they bogusly discredited him and dragged his name through the mud.”

Although more and more people are beginning to understand that the use of nuclear weapons could obliterate the planet, modern slang throws around the use of “bomb” in a euphemistic, or even positive light.

“‘Blonde bombshell’ and it’s the bomb — these are all terms that come from the bomb that bested American culture,” Shertzer said.

And yet these terms are used without a second thought to the horrors of their effects. Think about that the next time you “bomb” your math test.

The final line of the film is spoken by Oppenheimer, admitting to none other than Albert Einstein that the creation of the atomic bomb set off a chain reaction that could bring the world to destruction.

The film found a double meaning in Oppenheimer’s sentiment. Not only was the nuclear reaction so devastating, but the proof that the atomic bomb exists — that humans can harness the destructive capabilities of nuclear energy — ignited a race of global superpowers to maintain control of such a weapon.

Nine countries have nuclear weapons that have the potential to demolish the planet if used. Because of Oppenheimer’s creation, the human race lives closer to its own self-destruction than ever before.

How could the use of nuclear power, something of such destructive and brutal nature, possibly be morally justified? Some pin the guilt on the fact that nobody is entirely responsible.

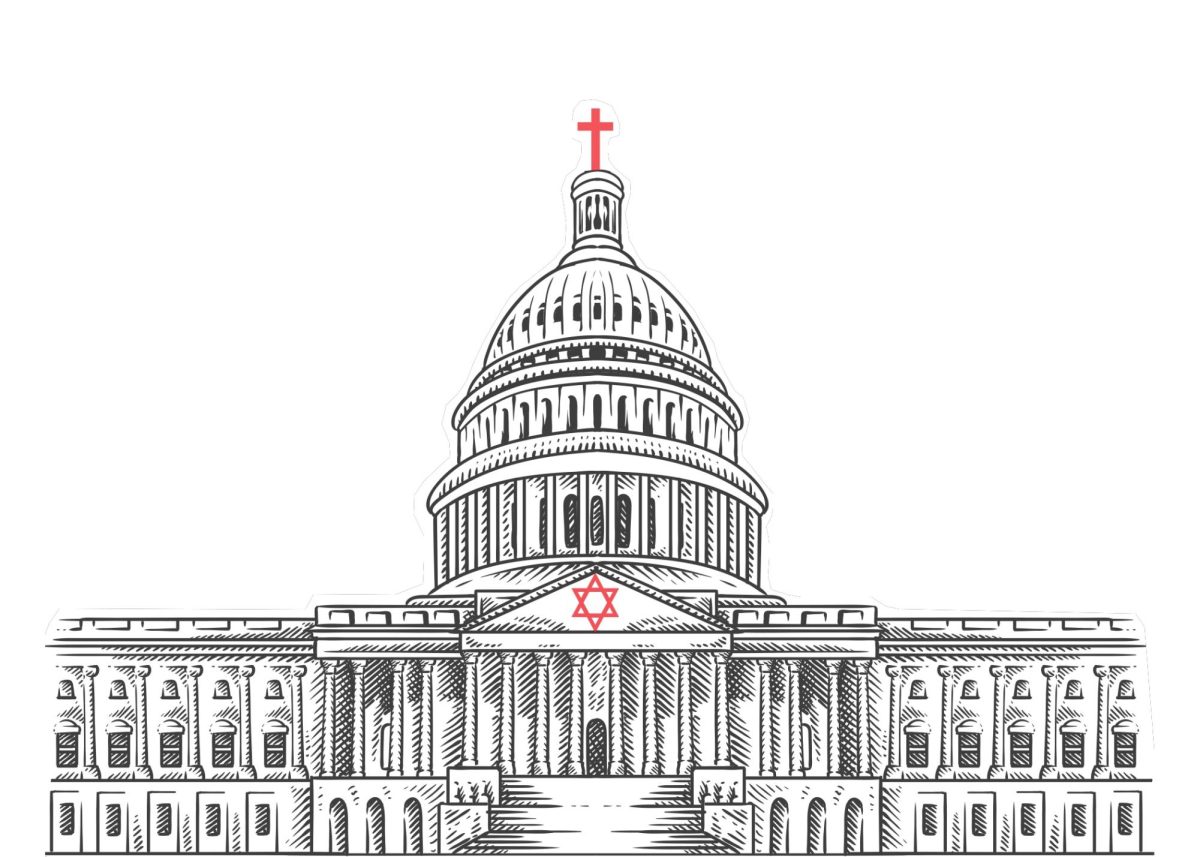

Oppenheimer, his team of scientists, President Truman, government and military officials, the pilot — all these people played a part and none are solely responsible. Others — like President Truman — put the power in God’s hands. They claimed that He gave Americans the power of the bomb, so they had the right to use it.

“We thank God that [the nuclear bomb] has come to us, instead of to our enemies; and we pray that He may guide us to use it in His ways and for His purposes,” Truman said in the Radio Report on the Potsdam Conference.

Still others justify the use of the bomb by claiming that dropping it was the only way to end World War II, ultimately saving lives.

“You could justify that in World War II by saying that the Japanese wouldn’t surrender,” Shertzer said. “There’s some truth to that — in fact, there’s a lot of truth to that. But you could make a similar justification for any conflict. And then we arrive at a place where nuclear bombs are going off all over the place and we’re done. It’s a really dangerous type of thinking.”

Trying to justify extreme violence leads closer to abandoning safety measures and laws.

After he witnessed such destruction, Oppenheimer tried to teach the world that in the future, ethics must go hand in hand with science before humans annihilate themselves.

J. Robert Oppenheimer, self-proclaimed “destroyer of worlds,” understood the magnitude of his actions when it was too late. Like Prometheus, Oppenheimer gave humans something that perhaps they were never supposed to have: the potential to destroy themselves.