Saudi Arabia’s 170km City

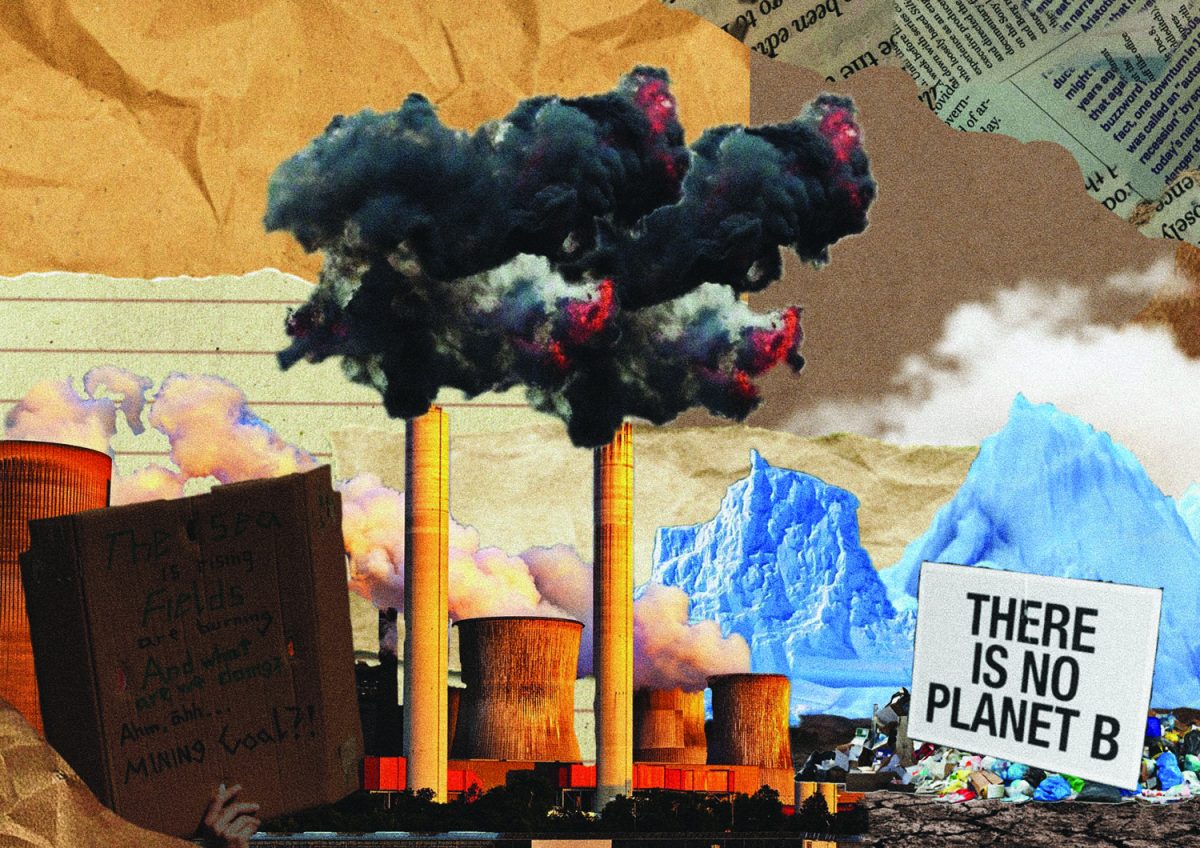

Saudi Arabia’s vision for a line-shaped city blurs the line between dystopia and utopia.

June 16, 2023

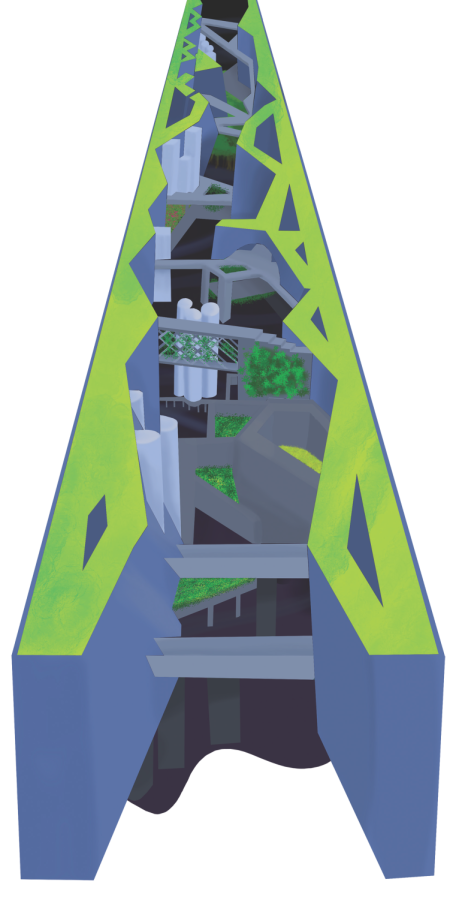

Imagine living in a massive, reflective skyscraper. A long– 170-kilometers – city riddled with technological advancements unseen in American society. The Crown Prince of Saudi Arabia, Mohammed bin Salman, proposed just that in a promo video as part of the Neom development project. A formidable mega-city to hold 9 million residents, titled “The Line,” is a part of the government’s ambitious plan to attract tourists to their country with high walls, hanging gardens, and an overall futuristic aesthetic.

Stretching from the Red Sea across a barren desert, the architectural layout of The Line is supposed to be made of gigantic mirrored walls. This eerie contrast to the open land surrounding the area, hardly touched by civilization, symbolizes human evolution in the natural world. This project is designed for the country’s 2030 vision, outlining Saudi Arabia’s plan to restyle the geography, diversify the economy, and signify a revolution in modern living.

Though the released architectural details are limited, those who designed The Line claim that it will run entirely on clean, renewable energy. No roads, no cars, no carbon emissions. High-speed rails that will make it accessible to travel from one end of the city to the other within 20 minutes. Hospitals, markets and businesses all within a 5 minute walking distances.

Artificial intelligence said to be incorporated in every aspect of communities, including robot maids, flying drone-powered taxis, and a giant artificial moon, while also maintaining greenery and gardens. The designs for the city’s vertically layered communities model bin Salman’s idea of enhancing human livability: “The Line will tackle the challenges facing humanity in urban life today and will shine a light on alternative ways to live.”

Bin Salman’s vision encapsulates the idea of perfect, easy living. So why wouldn’t someone want to live there? Because this utopian dream designed by the Saudi government is, in reality, a dystopia. This idea can be seen in books like “The Hunger Games,” “Divergent,” and “The Maze Runner,” in which creating a perfect utopian world can be more harmful than it seems. Junior Grace Trautwein, an avid reader, relates President Snow in The Hunger Games to bin Salman: “dystopian leaders think that they are doing the right thing by creating their ideal world, which is always unsafe for the citizens. Achieving a utopian society is impossible, in books and in real life.”

Through literature, today’s society has been introduced to the flaws of humanity and the negative consequences of dystopian worlds. Dystopian societies are attempted utopian societies that have failed due to societal flaws. Such flaws, in books and in real life, are what distinguish utopian and dystopian cities, typically having relations with poor human rights and human-created environmental damages. The Line shows potential to execute both of these flaws once the city is constructed.

The Line’s isolation from the rest of the world reminds Director of Teaching and Learning Anna Alldredge of a dystopian novel. “When reading up on the Line project, I am reminded of ‘City of Ember’ by Jeanne DuPrau. Similarly, the citizens lived completely inside and did not have exposure to the natural elements of the outside world.”

This isolation not only lacks human connection to the natural world, but it also makes the city’s inhabitants more prone to being controlled by technology. While residents and visitors bask in this futuristic paradise, they will be subject to heavy surveillance, such as a data-gathering network connected to facial-recognition drones.

Heavy surveillance and little privacy can significantly harm the livelihood of marginalized Saudi Arabian groups, such as women or the LGBTQIA+ community. Discriminatory laws and practices heavily enforce Saudi-Arabian women.

The LGBTQ+ community also suffers from no protection rights, making it illegal to marry the same sex.

“The Line will become a wasteland. Foreigners won’t want to live there, and minorities won’t put trust into their government,” sophomore Eleanor Crafton said. “At the end of most dystopian novels, these governments get overthrown, such as in Divergent. The city can’t thrive when pushing laws that the citizens are against.”

If Saudi Arabia is already plagued by having no human rights, what makes The Line any better?

There also lies the problem of forced eviction. The Line is supposed to be built over land that is already home to the Huwaitat tribe.

The crown-prince, having already started the process of deporting the natives from their land, shows how little he cares his own people, much like a dystopian leader.

Twenty thousand people now face eviction, without a place to go or any compensation. The Line is simply an attraction to bring tourists to Saudi Arabia, which will result in who have lived there for generations.

And while the Crown Prince claims that this city will be extremely environmentally friendly, this statement has been found very doubtful considering that the country is one of the largest oil-producing countries. Creating a city that produces zero carbon emissions sounds like some joke to environmentalists and to anyone who has read about technologically advanced cities, which tend to lack greenery and clean air.

The designers of this city have thrown aside the issue of native land, environmental effects, and the danger towards minorities. The flashy features do little to cover up the environmental and moral issues regarding this city.

However, this isn’t the first dystopian recreation we’ve seen. Other billion-dollar super projects, that were supposed to change the way of urban living, had been abandoned or failed.

Dubai’s Nakheel Harbour and Tower and North Korea’s Ryugyong Hotel were both never completed due to economic slumps, and China’s Mongolian city of Kangbashi only homed 10% of what they had hoped for.

The Line proves to be nothing but another dystopian novel waiting to happen. A vanity project, to bring tourism and money to bin Salman’s country, is doomed to suffer the same fate as the mega-cities before it. This has all been seen before.

“I read dystopian novels all throughout middle school,” junior Lucas Acosta said. “Those authors have taught me, and the rest of the generation who have grown up on those novels, how to differentiate a dystopian from a utopia.”