Why Do We Procrasinate?

“Not not right now, I’ll just do it later,” and “Why am I such a procrastinator” are just a few phrases that run through our heads when burdened with unwanted responsibility, but what does it mean to procrastinate and why are students so prone to do it

April 4, 2023

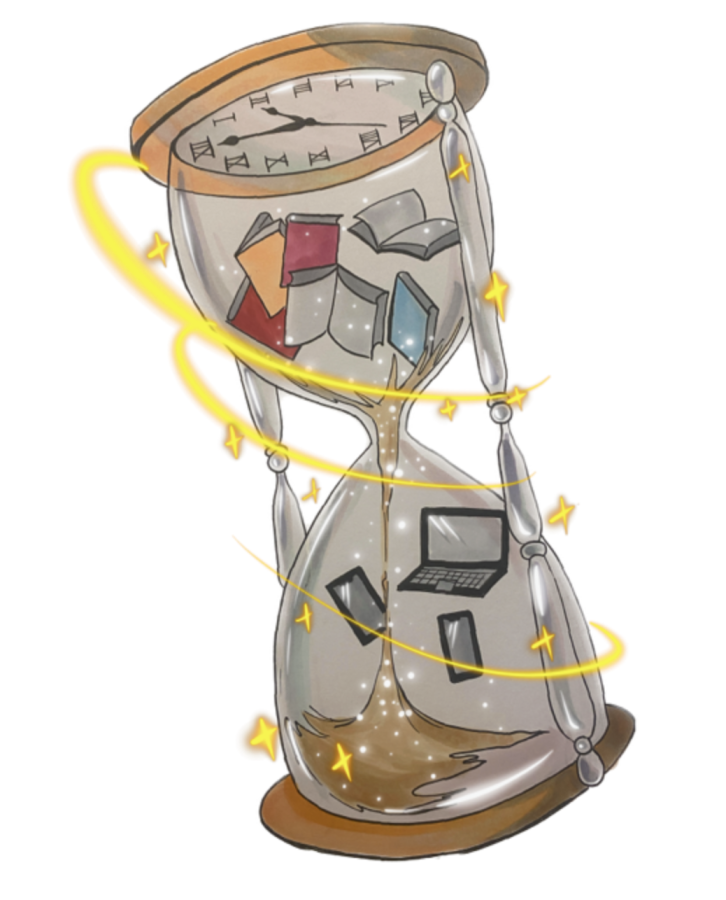

The textbook definition of procrastination derives from the Greek poet Hesiod dating back to 800 B.C., who warned his fellow peers not to “put your work off till tomorrow and the day after.” Prevalent in all adolescents and adults, whether in the workforce or a school environment, procrastination is simply defined as delaying or postponing something.

Procrastination continues to have a tight hold on us, inducing emotions of frustration or even self-inflicted fear if not understood and helped. You’re not a bad student, a lazy kid, or simply going mad; it’s merely something people experience to the right and left of you. This action of procrastination is universal because it’s our brain’s nature and function. According to UPMC HealthBeat, procrastination is “the avoidance of work or necessary tasks by focusing on more satisfying activities that are due to a chemical in the brain.” So what happens explicitly in our brain when we procrastinate due to this so-called chemical?

Science describes it as a battle between the limbic system and the prefrontal cortex. In charge of the unconscious and pleasure area of our brain, the limbic system opposes the prefrontal side, known as the voice of internal reason or “planner.” With a high probability of the limbic system winning, our human brains are prompted to delay doing essential responsibilities that could and should be finished—to experience a temporary relief of not needing to do something you dread. Dr. Pychl describes this as an automatic “immediate mood repair” compared to the weaker prefrontal cortex, which combines information to make decisions. Situated behind the forehead, the prefrontal cortex is similar to an angel sitting on your shoulder, reminding you to be productive and to get work done; however, it is not automatic like the limbic system. In order to kick-start your prefrontal cortex to function, you have to shift gears to tell yourself ( “ I have to focus and finish writing this journalism article.”). However, if there is a lack of affirmation, you are left consciously unengaged in an assignment. In that case, the limbic system will dominate, rewarding you with what you want to do instead of writing this article-leading you to procrastinate.

So if procrastination isn’t about laziness, then what is it? Connecting back to the ancient Greek word akrasia- procrastination isn’t just freely delaying a chore or an assignment but instead the action of doing something against our better judgment. At the University of Sheffield, Dr. Fuschia Sirois believes, “It doesn’t make sense to do something you know is going to have negative consequences.” In our brain, procrastination isn’t just a major flaw or a known psychological curse on our time management skills but an outlet to help us cope with tough and pessimistic emotions associated with specific responsibilities- such as stress and self-doubt. Just because you procrastinate does not make you lazy; as Dr. Pyschyl puts it, “[procrastination] is an emotion regulation problem, not a time management problem.” The reason for our aversion will fluctuate based on the responsibility at hand. Tasks such as writing an essay, cleaning your room, or washing dishes have a higher rate of procrastination due to their level of dreadfulness. However, underneath that, we might be experiencing negative emotions associated with that specific task, such as frustration, street, insecurity, or self-doubt.

When looking at a blank assignment, do thoughts of “ I can’t do this because I’m not smart enough” or “I am so dumb” come up? If these thoughts pop up, then the idea of procrastinating remains wrapped around our fingers, blocking us from achieving our full potential and productivity. Here are some ways to counteract procrastination and instead increase productivity:

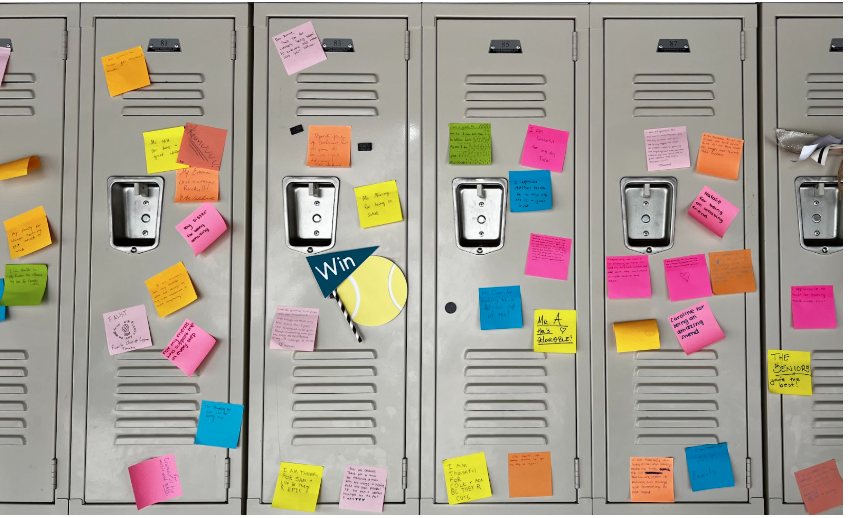

1.) Don’t catastrophize ( have a positive mentality by saying affirmations such as, “ I don’t like doing this, but I can get through this”)

2.) Pomodoro method (break up your tasks into smaller intervals like 25-minute stretches of academic work that can be rewarded with 5 minutes of break)

3.) Reward System ( Set aside a reward like going on your phone or a snack after you finish your tasks so that it is both rewarding and strengthening good habits)

4.) Be Gentle To Yourself ( Don’t be hard on yourself for what you didn’t do, but instead look ahead as a source of motivation to be more productive)