The Crumbling of Theocracy

While Iranian civil rights spread throughout the globe, the political stability of Iran’s theocracy is beginning to erode.

February 21, 2023

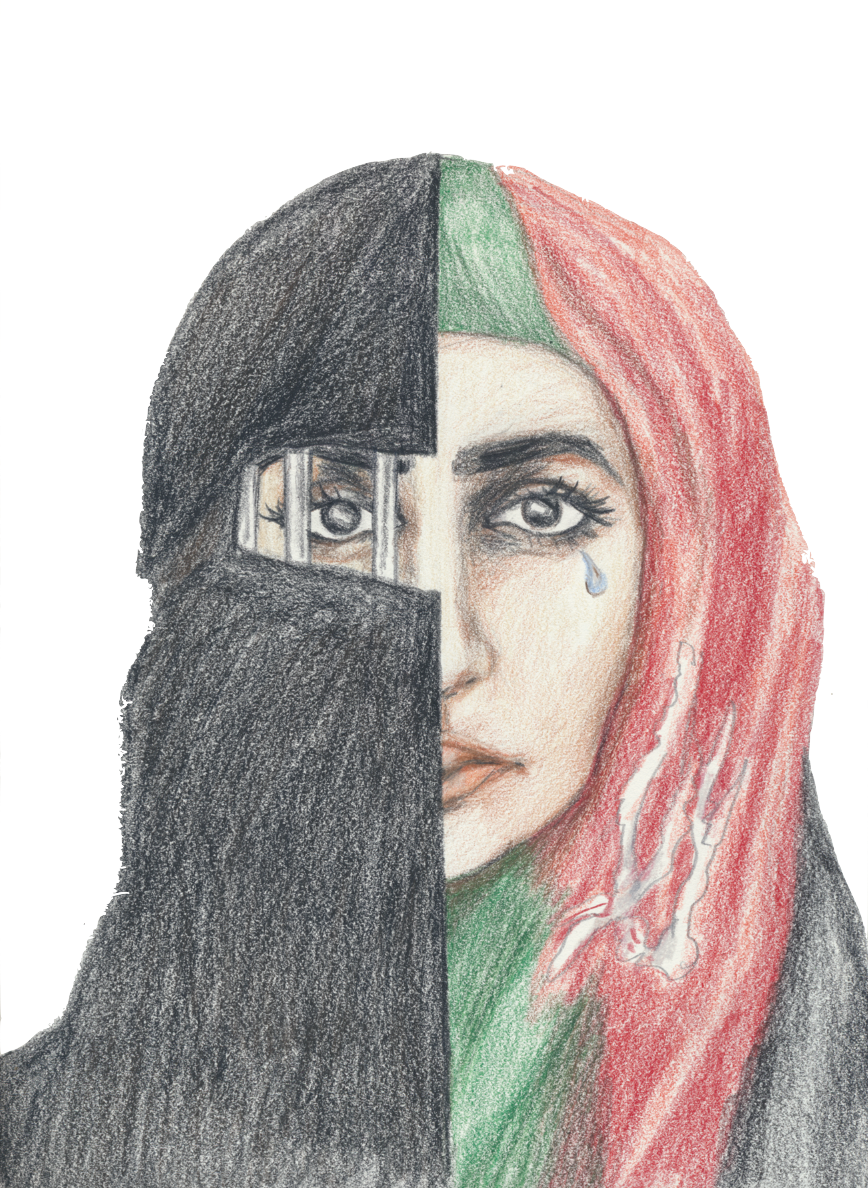

With the recent abolishment of Iran’s stern and religious morality police and worldwide protests pressuring Iran to reform its religious policies regarding hijabs, what is stopping this liberal momentum from dismantling Iran’s theocratic and fundamentalist core altogether?

Before Ruholla Khomeini, Iran’s first Ayatollah (supreme religious leader), Iran was a secular state run under the monarchical rule of the Shah—whose reign lasted for over a millennium. In fact, according to Laguna Social Science Instructor Dena Montague, “women were banned from wearing hijabs by the Shah in an attempt to modernize with the rest of the world.”

However, the Shah’s vision for modernization happened to be heavily funded by American oil money. And as a result of this, many Irani nationalists propagated the idea that the Shah was a puppet for western powers seeking to spread influence over the middle east, which resulted in growing public disapproval of the Shah’s reign. A violent revolution in 1979 brought a conservative Muslim scholar, Ruholla Khomeini, out of exile and to the helm of the power vacuum in Iran after the Shah and his wife escaped to the United States.

Interestingly, Khomeini initially protested against the Shah’s absolute power over Iran, but when Khomeini realized that absolute power would be the easiest way to instate his religious beliefs on a national scale, his ideologies changed.

According to Montague, Khomeini gained his majority using radical Shia Islamic rhetoric that “distinguished Shia Islam from Sunni Islam, mostly over arguing that they had a direct lineage from Mohammed the Prophet.”

“During this time,” Montague said, “is when you begin to see a huge split between Sunni and Shia relations, both politically and culturally.” As he grew in popularity, Khomeini fueled Shia “distinguishment” from Sunni Islam and used Shiite values “as a means in 1979 for political solidarity, nationalism, ethnocentrism, and oppression,” Montague said. Unfortunately, Iran’s theocratic government still uses Islam as a political tool today.

“The regime has time and time again used both religion and women as tools to project pressures of conformity. This can be seen in how Iran forces women to wear hijabs in order to identify as good Iranian citizens and Islamites. Internationally, Iran has also used its Shiite views to create tension with its political enemies, such as Saudi Arabia and Syria through its religious differences,” Montague said.

“From my understanding, it wasn’t Islam that created such extreme tensions between middle-eastern states—it was the state that used it as a tool to create nationalism and spread influence around the region, particularly into Iraq and Pakistan. I feel like there should be a distinction between how religion is used as a political tool for oppression, and how religion exists for people to find some sort of happiness or meaning in life,” Montague said.

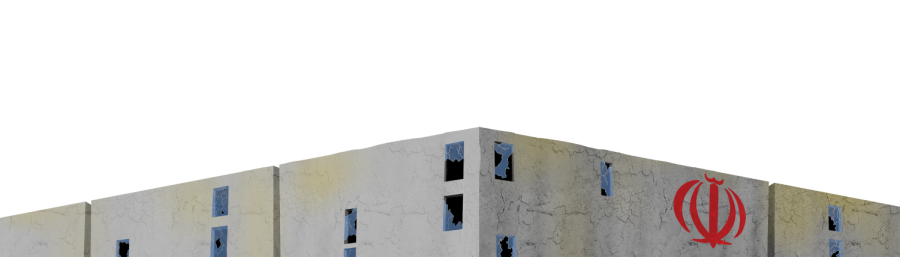

But with these recent uprisings occurring both in Iran and all around the world, the stability of Iran’s political climate has been significantly weakened. According to The Global Economy, a website that collects international political, economic, and business data, Iran’s political stability index, which is measured from -2.5 to 2.5 based on the likelihood of a revolution, has decreased from -0.81 in 2016 to -1.62 in 2021.

Iran has combated these likelihoods by embedding core regime values in their education system. According to Sara Damavandan’s article in IranWire, “Islam is a central tenet of Iran’s education system.”

“Not only has religious education become one of the most important subjects in the classroom, but religion has also become central to the teaching of history, language, social studies and the sciences,” Damavandan said.

This is how they control their population and maintain both their authority and legitimacy as a state. This is by no means a new method — autocratic regimes in the past have done and still do the exact same thing. Theocracy is rooted in education. If a theocratic regime is unable to provide its citizens with the core tenets of their religion, that regime will fail to keep its population in line.

Around the world, countries have implemented policies that separate the church and state in order to avoid the situation that Iran has found itself in. Here in the United States, it is written in the Bill of Rights. However, fundamentalists still find loopholes in legislation to insert religious ideologies into state education. Such ways include religious student-run clubs, faith-based after school programs, and even sponsoring school sports teams.

With a new and upcoming generation influenced by technology and its unlimited sources of information, it is becoming more and more difficult to discern fact from someone else’s reality or faith. The importance of separating state education from religious affairs is more relevant than ever.

According to Assistant Regional Director of ADL Santa Barbara/Tri-Counties, Ashley Myers, “public education is one of the most important resources that we have in this country. For its success — and thus in turn the subsequent success of our nation — students of all backgrounds should feel that they belong in their classroom.”

For the sake of our government, and many others, religion cannot be weaponized through education to destabilize. The repercussions in Iran have made it clear that religion, more often than not, is an overall oppressive governing mechanism. The fact that Iran’s citizens have the courage to protest a government that is using their own religion against them as a means of control is a momentous step in stabilizing the middle-eastern region.

In the midst of these recent Irani protests, it is most important to note that it is not the Islam religion that is being protested, but the way that the government is using it. “Most people in the world just want to live free, and for the most part countries don’t use religion with bad intent as Iran does,” Montague said. “Islam is centered around peace and empathy, but the government’s interpretation of Shia Islam contradicts it.”