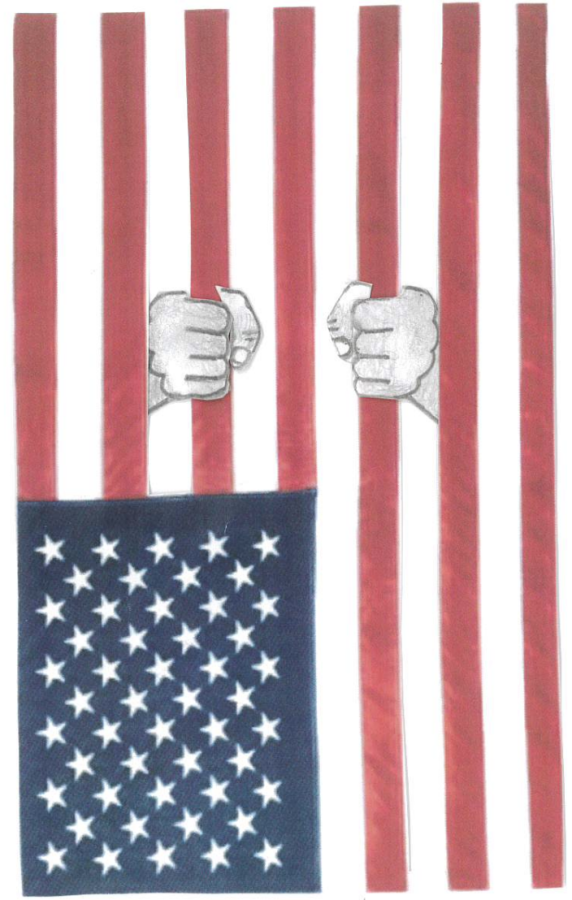

Criminal Justice Reform

The reincarnation of the racial caste.

June 17, 2022

The United States is the world’s leader in incarceration rates. The nation holds up to two million men and women who have committed wrongful acts according to the nation’s criminal legal system. The United States makes up less than 5% of the global population, but our prisons hold approximately 20% of the world’s prison population.

The corrupt system of mass incarceration upholds the centuries-long racial caste system that has succeeded in the United States since the first colonizers. Since slavery reigned in the U.S., there has been discrimination and race-based hatred in our hyperpolarized society.

It started as slavery and the TransAtlantic Slave Trade that unwillingly brought over around 12.5 million Africans on the Middle Passage and exploited them for labor.

After the Emancipation Proclamation was established in 1763, African Americans were freed from slavery—but not discrimination. As soon as 1777, there were new segregation laws notoriously labeled as “Jim Crow” laws. Jim Crow laws were state and local statutes that legalized racial segregation and enforced racist attitudes and prejudice, especially in the southern states.

After decades of segregation, continuous boycotts, and civil rights activism, the so-called “second institution of slavery,” was legally banned and declared unconstitutional in the country. That was 1964.

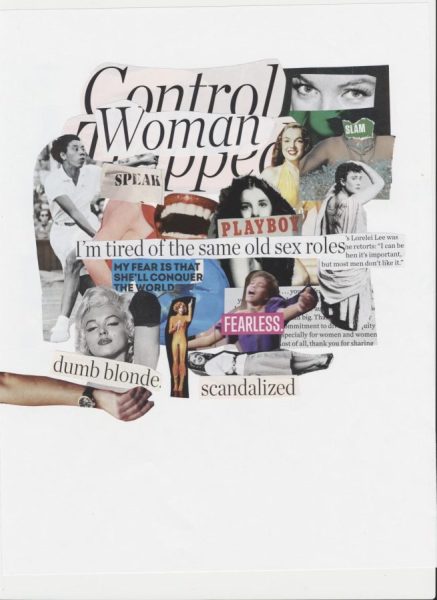

Today, there arises not only a new form of racial discrimination but one that disproportionately victimizes and mistreats people of color in the United States. “The New Jim Crow,” a phrase coined by author and civil rights activist, Michelle Alexander, is the term used to describe this reincarnation of the racial caste.

Mass incarceration. Is the unique way the U.S. has locked up a vast population in federal and state prisons, as well as local jails. The fact is that the U.S. incarcerates more people than any nation in the world, including China. The disparities among Black and Latinx people imprisoned in the United States given their overall representation in the general population are staggering.

“The term is a reference to all the systemic injustice towards people of color that has intentionally been embedded into society today. It is the new and legal way of continuing the marginalization and discrimination towards people of color and specifically Black people that was set up after emancipation and the failed Reconstruction,” said Victoria Dryden, English Department chair.

Furthermore, our judicial system is inefficient and biased. Men and women who have not been convicted of a crime, sit in overcrowded and understaffed jails waiting for their day in court.

For example, inmates in Chicago’s jails in 2015 served the equivalent of 218 years more time waiting for trial than the sentences they would ultimately be given. Housing the inmates for this extra time costs taxpayers $11 million.

But the money is the least of it. Consider Kalief Browder, a 16-year-old from New York. He was wrongly convicted of a petty crime and sent to prison waiting for a court date. Browder spent three years in prison at Rikers Island–including two in solitary confinement–before his case was dismissed. The trauma of those years alone behind bars lingered. At 22, Browder committed suicide.

America’s approach to punishment and rehabilitation consistently lacks a public safety rationale, inordinately affecting minorities, and administering sentences, even for petty crimes.

While just touching the surface of the large issue at hand, mass incarceration poses the largest threat to continued prejudice and racial discrimination in this country. The issue of mass incarceration has a rich history that starts during Nixon’s presidency.

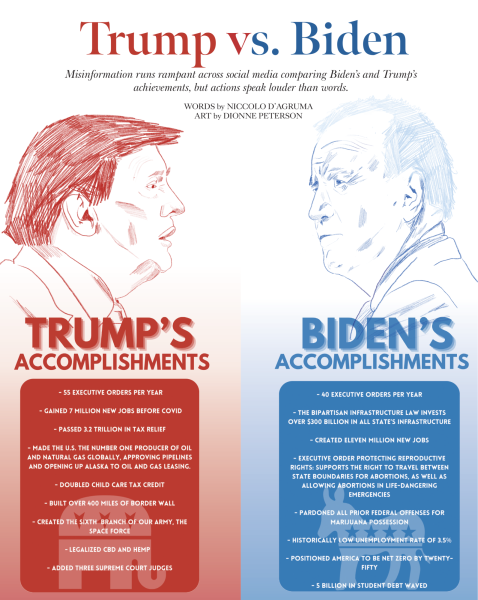

The prison population began to grow in the 1970s when politicians from both parties used fear and racist rhetoric to administrate increasingly disciplinary and “corrective” policies. Nixon spread this divisive ideology, declaring a “war on drugs” and justifying it with speeches about being “tough on crime.”

The prison population skyrocketed during Reagan’s administration. Reagan took office in 1980 and the total prison population stood at 329,000. By the end of his eight years in office, the prison population had almost doubled, to 627,000.

Due to Reagan’s rhetoric claiming “law and order” represented true American ideals, the prison rates rose. This staggering rise in incarceration rates affected people of color the toughest, for they were disproportionately imprisoned then and remain so today.

“The War on Drugs was a political manipulation to gain political support during elections,” said Dryden. “The whole criminalization of Black men that started after the Civil War fed into the need for a “War on Drugs.”

The problem is that the very people who were criminalizing Black men and people of color were also, not only supporting drugs being siphoned into marginalized communities but also making sure that incarceration punished them, broke up their families, and fed the fire of poverty, crime, and powerlessness that resulted.”

While mass incarceration is a new tactic of discrimination, there is a growing cause and plan against mass incarceration, which ranges from those like Michelle Alexander, author of “The New Jim Crow,” who argue that the way the country has filled the prisons is established to discriminate African Americans directly, to business people who can see that as a policy and growing institution, mass incarceration isn’t working.

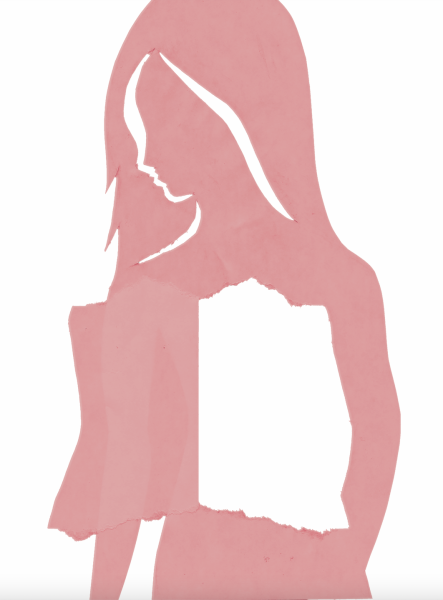

This increasingly more normalized system has proven to set convicts up to re-enter society broken and unable to have a normal life. From the inability to vote, get food stamps, and get a job, many ex-convicts are set up for failure when they walk out of prison.

“If you weren’t broken when you went in, you will be when you get out,” Dryden said.

Evidence suggests that being locked away scars, stigmatizes, and damages inmates. The economic hardship and lingering mental issues that ex-convicts face are detrimental to their future success.

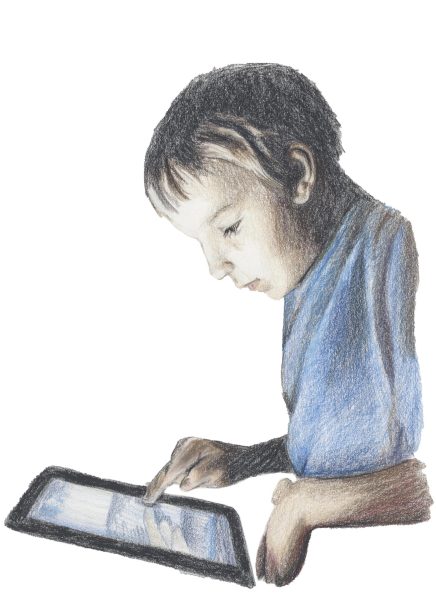

While the future of mass incarceration seems dark and destitute, education is a powerful tool students and people can use to spread information about mass incarceration and “The New Jim Crow.”

“There are people that sacrifice their lives to make a difference and to educate us and to bring change,” Dryden said.

“It is so important for young people, all young people, but also Laguna students who have privilege and access to learn about these things and to make it a part of their journey to force change. This country is in a crisis right now. The next generation holds the most power for change.”