The Rise of STEAM

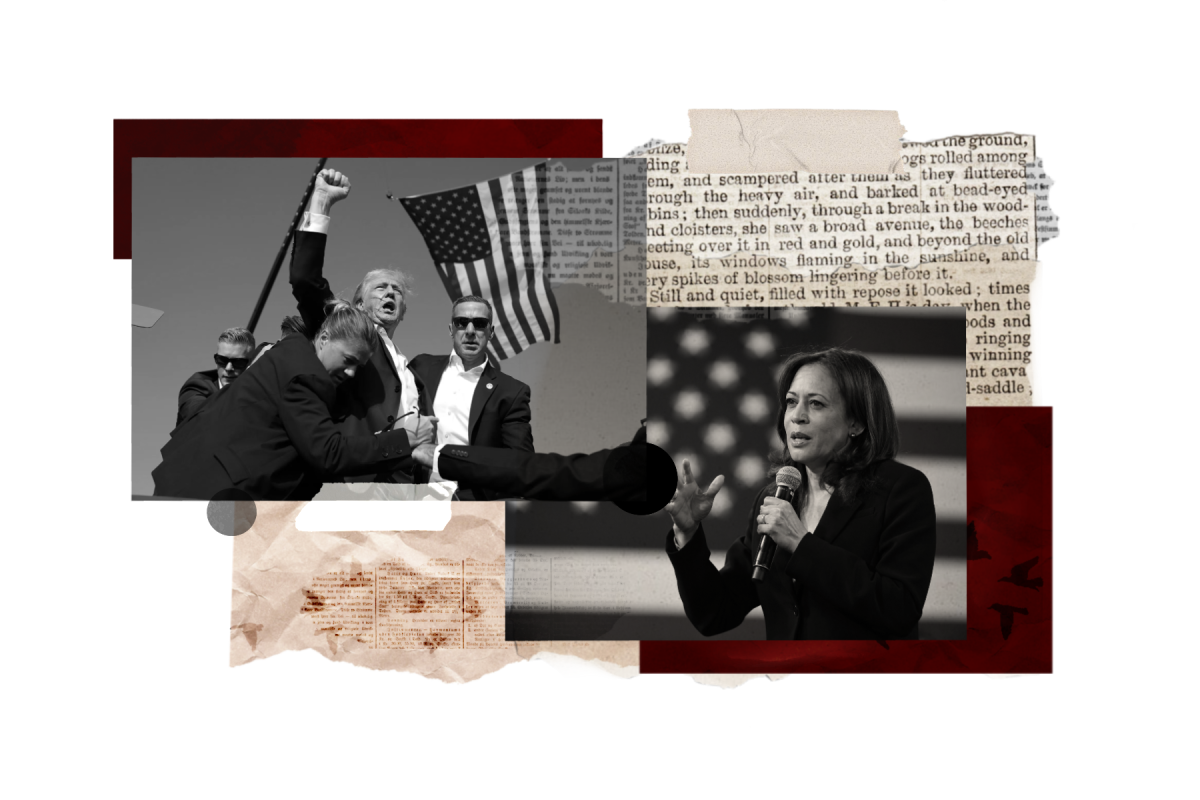

The age-old friction between analytical minds and creative thinkers comes to a head in our modern age of advanced technology and innovation. Where do students and teachers stand? How does society play a role in influencing education? And, most importantly, how can the education system move forward with such discord? And the topic? STEM versus Humanities.

June 10, 2021

The die is cast. The lines are drawn. Society picks sides, spitting arguments across a widening chasm of dysfunction and disagreement.

There can be no doubt that STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) “enjoys a definite advantage when it comes to funding and popularity at this moment,” said Humanities Director Dr. Charles Donelan, “b ut I’m not convinced that this moment will last.”

ut I’m not convinced that this moment will last.”

Especially today, in the age of exponentially-advancing technology, schools and businesses alike sing STEM’s praises. Of course, perception does take a hand in this societal imbalance.

“There are stigmas to both. I don’t know how we begin to disassemble them,” said Upper School Head Melissa Alkire.

Whether due to parental pressure or the fear of college admissions, students feel the need to beef up their transcripts with STEM-focused courses and APs. “All these stigmas hurt our ability to think critically and be analytical and creative,” Alkire said.

But, perception–no matter how unfounded–is usually based upon a kernel of reality, and in the case of STEM hype, the reality is a strong argument.

“I think it really is for practical reasons,” STEM program director Staci Richard said. “I’m sure the range in humanities is wide too, but I think it’s the practical nuts and bolts: we need vaccines, we need to figure out our energy grid and what sustainable energy looks like.”

The path of an artist or writer or historian is more shrouded than that of a medical professional or science researcher.

“There is a clear linear [progression]” for STEM students, explains Alkire, “At the end of my history degree, I didn’t have interviews at history firms; they don’t exist!”

This simple truth provides universities across the globe a justification for their emphasis of the sciences.

The American Affairs Journal stated that, in 2018, the U.S. spent more money on STEM education than “the entire Israeli military budget.”

And, like ducklings waddling after their mother, secondary schools “mimic the priorities of higher education” and will “likely continue [to do so]” Donelan said.

Laguna is no exception. With the construction of long-promised science facilities on the upper school campus, “Laguna has focused on building out STEM,” Richard said.

But the issue is not isolated to societal perceptions and external pressure. As a self-proclaimed humanities student, junior Sofia Anderson notices the disparity between the arts and sciences; “There is definitely a stigma associated with STEM more so than the Humanities Department.

“STEM is based on subjects like science and math which consist of rules, theorems, and facts so there is not as much room for creativity.”

Whether it is acknowledged or not, there is an underlying perception that some students are good at science and others predisposed to the arts often, those stereotypes go hand-in-hand with gender divisions.

Students who display analytical thinking are self-proclaimed as scientists or mathematicians or non-creatives.

“There can be people that are interested in both,” junior Zoë Stephens said, “but I think they lean one way more than the other.”

Students who express interest in both fields usually feel pressured to pick one or the other.

For this reason, labels are counterproductive. According to Donelan, “The right-brain, left-brain distinction strikes me as an oversimplification. Good scientists are creative, and good artists understand the world in a way that’s at least partly scientific.”

Therein lies the crux of the issue. This intellectual split between the analysts and the dreamers is a man-made artifice—an invisible line in the sands of culture.

The current climate might celebrate STEM accomplishments, but without the context of history and the enriching culture of artists, musicians, and writers, humanity’s accomplishments are lackluster.

“For example, without the ability to explain science to non-scientists in a way that’s convincing and capable of changing people’s minds, important scientific discoveries risk being ignored or contradicted for reasons that are not only irrational but also inhumane,” Donelan added.

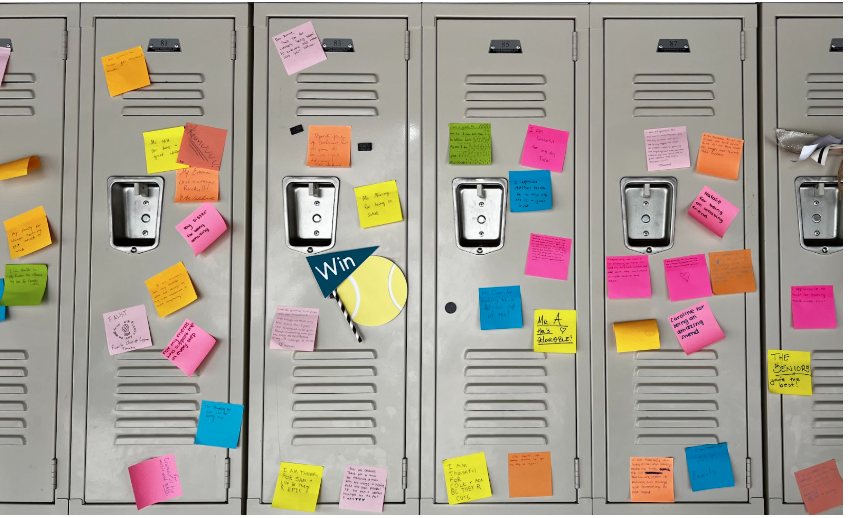

Many teachers work towards incorporating STEM into their humanities courses and vice versa, attempting to marry the two subjects.

“I do think we need to get rid of labels and build out the humanities,” Richard said.

“Look at Ashley Tidey’s work with Urban Studies. Just broadening our definition of humanities.”

In striving for this happy medium, Richard counsels students who feel pulled toward both fields and does her best to find this inter-disciplinary harmony. “Personally, I would love to find all sorts of space for the intersection of those two things.”

Regarding academic pressure and the worry of college admissions, Alkire said, “We have to throw out that worry. If you can say that ‘I took these humanities courses because they made me a better person, a better thinker, and a more interesting, creative human being,’ that’s a much better story than ‘I took all my APs.”

A robust knowledge of STEM subjects is more and more crucial to every professional field–no one can deny its rising importance.

Some argue that the humanities approach irrelevance—that it’s lunacy to add “A” for arts to the STEM acronym.

But, since there is no true split between the STEM and humanities fields, the current surge of technology precipitates the rising need for historical and cultural context. “We need to be able to engage on that human, ethical line,” Alkire said.

To that end, the time has come to abandon the inane distinctions—to leave STEM and Humanities in the dust—and make way for the brainchild of both: STEAM.