SMALL WORDS. BIG IMPACT.

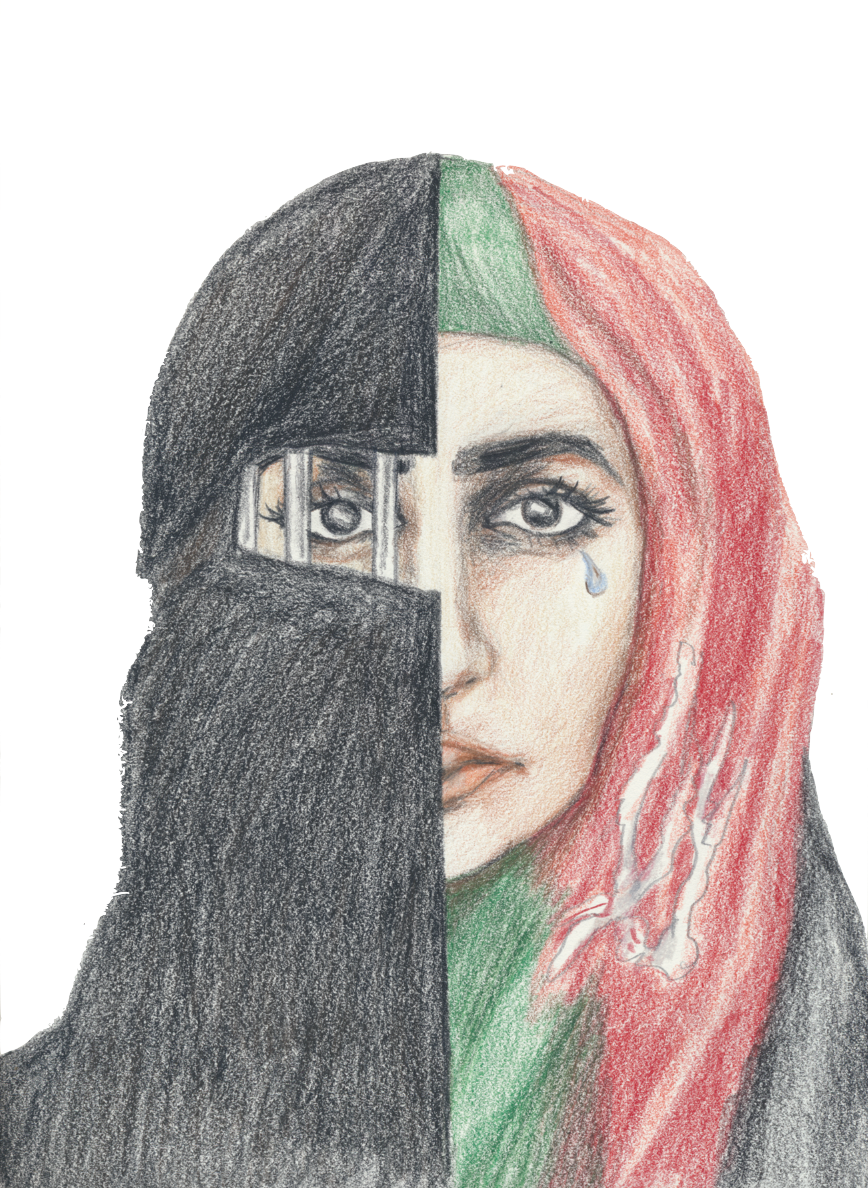

The racism we all overlook.

May 4, 2017

Columbia professor Derald Sue defines microaggressions as “brief and commonplace daily verbal, behavioral or environmental indignities that communicate hostile, derogatory or negative racial slights and insults toward people of color.”

In other words, a transgression not as blatant as a hate crime, and one that has enough deniability – “It was a joke!” – to be considered excusable.

Because of the desensitization our generation has undergone to various racial slurs (“n****r” and “bea**r” are dropped in everyday speech), microaggressions are difficult to spot at first.

A microaggression isn’t intentionally hurtful. But to be on the receiving end of one stings and leaves you to wonder: should you speak up?

A microaggression can come in many flavors: mocking, appropriating, patronizing and fetishizing, to name a few.

It’s the racism that seeps into our regular conversation and reinforces stereotypes and discriminating behavior.

An obvious offense is making fun of another’s race (so obvious, in fact, that it might qualify as a full-fledged aggression instead of a micro one).

This might include imitating a person’s accent or mocking one’s physical appearance: “I look so Asian,” someone laughs when they’re caught blinking in a photo, or someone mimics and exaggerates a Mexican accent for comic effect.

Racist mimicry takes the shape of cultural appropriation, as well. Appropriating isn’t necessarily the same as mocking, as its main purpose is not to be funny.

The issue here is that appropriating another’s culture typically disrespects it by making light of honored traditions just because they’re trendy.

Every Halloween there’s at least one “Sexy Indian Princess” dressed in something skimpy barely resembling traditional Native American clothing.

If the person was wearing this out of respect for the outfit’s original purpose, it would be a different story. More often than not, though, this is not the case.

A more benevolent form of microaggressions is patronizing – I say benevolent because most of the time, the aggressor’s intention is to be helpful.

Patronizing most often manifests as treating a person of color as if he or she doesn’t speak the native language or doesn’t understand local customs.

While there is a time and place for helping someone learn, it is condescending to make an assumption that a person is unfamiliar with English based purely on race or appearance.

Social Science Instructor and Head of Middle School Stephen Chan recalls how people frequently “compliment” him on how well he speaks English.

“For me, [I] might be having a great conversation with somebody, and then they come out with that: ‘You speak English really well,’” Chan said. “And all of a sudden, I feel like I’ve been diminished in their eyes in some way, and it puts me on the defensive. So, the conversation no longer feels like it’s among equals, because now I feel I’ve been put in the position where I have to defend myself or justify myself.”

Another form of microaggression that hits close to home is racial fetishizing. Let’s take, for example, the common admissions of “I’d love to sleep with a black guy,” or “Asian girls are hot.” This isn’t the same thing as having an innocent preference in partners; it’s an othering, and it reduces a person to nothing more than their race.

On a personal note, racial fetishizing has perhaps affected me the most among said transgressions.

Recently, I became aware of conversation within my circle of friends where boys I’ve talked to were being teased about having “yellow fever.” That is, a fetish for Asian girls.

Hearing this reminds me that there are people who continue to talk about me, and other people of color, as if we didn’t belong — like we exist outside of a core white community — and who make me feel like my worth comes only from those who “have a thing for Asians.”

Head of Upper School Lolli Lucas weighs in, explaining the hardships of addressing these concealed insults.

“It’s difficult to withstand it and not know how to respond to it. And I also think it’s really hard because on the one hand, you don’t want to react in a way that’s overly dramatic, but on the other, you want to inform the person how hurtful that is.

She added, “I don’t know what age you have the strength and the stamina to do that . . . Because to be the person of color and always be the person educating is a really tough position to be in.

“There were only five black kids in my entire middle school, and so in most of my classes I was by myself and I didn’t want to be the voice of my race . . . I always questioned, ‘Should I be doing more? Should I tell somebody? Should I try to explain?’”

So what really is the problem with microaggressions? Hurt feelings? Yes and no.

Microaggressions create a sense of alienation for their victims. Once you are conscious of microaggressions, comments that once seemed small begin to feel enormous.

“The fact that I think about these things is the insidious nature of microaggressions,” Chan said. “It just gets in your head, whether it’s logical or not, whether it’s true or not, I still think about it. I think about it a lot.”

This feeling of isolation, and borderline paranoia, contributes to a larger problem of white supremacy.

If it seems that the perpetrators of microaggressions are white people, it is because, in our society, people of color are systematically disadvantaged and discriminated against.

Racism cannot be eradicated if attitudes don’t change first, and microaggressions are at the root of these attitudes. They send the message: “You are not like us. You are outside us and beneath us.”