Synesthesia in Art

Delving into art is a journey that few synesthetes regret—it brings the rest of us closer than ever to understanding how they see the world.

June 13, 2020

Stevie Wonder may be blind, but this doesn’t stop him from seeing vivid colors. When music enters his ears, it produces colorful visions in his mind, making him part of the 4 percent of the world’s population who have synesthesia. “Synesthesia,” or “union of the senses,” describes a fascinating neurological phenomenon: when encountering a stimulus, a second stimulus nonexistent in the outside world occurs in a synesthete’s mind, likely due to their greater neural crossovers in different sensory regions than the rest of us.

Through various combinations of the senses, there have been cases of 80 different types of synesthesia. Grapheme-color, seeing certain letters in certain inherent colors, is the most common type. Someone with this type may claim that the letter “J” is, in fact, a Tahitian sunset orange, or that “E” has always been Versailles gold. Laguna art instructor Dug Uyesaka recalls a former student who exhibited this type of synesthesia: “She was a creative and talented artist from the get-go but I think for her this just added another layer to her work.”

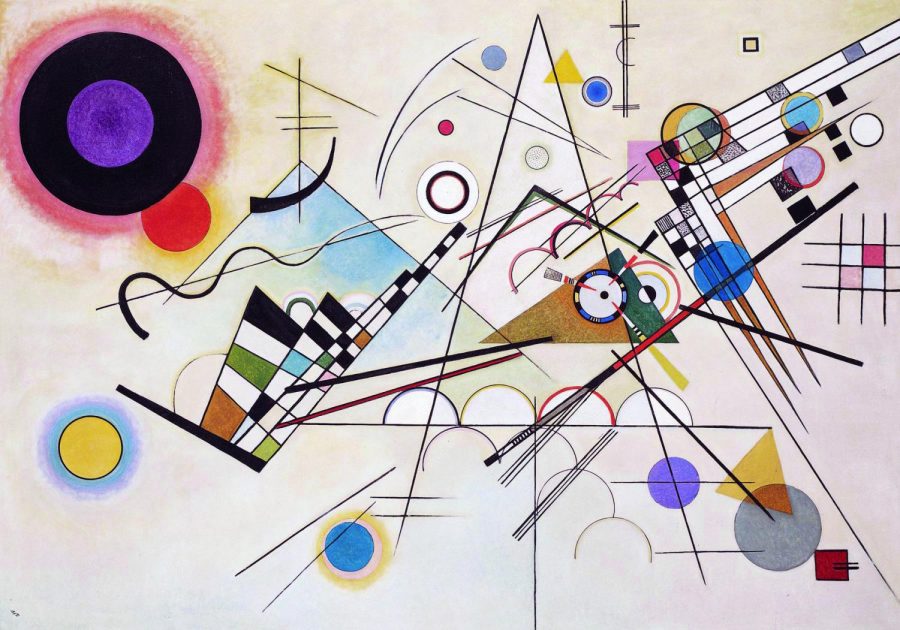

Abstract painter Wassily Kandinsky had another relatively common type, chromesthesia—sounds of music triggered visions of color in his mind, and vice versa. Though some say it can be a sensory overload, a disorder, and a curse, many synesthetes throughout history have taken advantage of their unique cross-sensory experiences as artistic inspiration.

“Synesthesia is seven times more common among artists, novelists and poets, and creative people in general,” said neuroscientist Dr. Ramachandran. “Artists often have the ability to link unconnected domains, have the power of metaphor and the capability of blending realities.”

This makes artistic hobbies and studies especially attractive to people who have this neurological trait. “I am just experiencing life through a heightened sense of iridescent form. It contributes to my artistry, as it does for all artists with synesthesia,” said synesthetic artist Jack Coulter.

He also said he was inspired by a group of abstract expressionists. This doesn’t mean that artists with synesthesia have an unfair advantage over those who don’t, though. Uyesaka says that synesthesia “does give them a very unique perspective on the world around them, but translating that vision is the same as any artist: individual expression, giving form to the unseen or formless.”

Seeing its display of a variety of bright colors and fanciful shapes, viewers may immediately associate synesthetic art with abstract art. Indeed, both share fundamental similarities in how they are created. Synesthetic experience played a major role in kick-starting abstract art, specifically abstract expressionism, in the 1940s.

This was when Kandinsky became the father of abstract art. Whilst abstract art encourages viewers to perceive beyond the tangible, synesthetic art shares with non-synesthetes another perspective of the world that has always been unknown and inconceivable to them. Abstract art abandons the pursuit of reality, preciseness, and logic. Neither synesthetic nor abstract art insists on an explanation, clear message, or narrative. Many pieces simply intend to evoke the viewers’ emotions or subconscious responses. Scattered lines, unrecognizable shapes, and discordant colors are the basic elements used to stimulate viewers’ spontaneous feelings. Rather than being given something recognizable, viewers now have the freedom to really feel the art without having to process its “intended message,” if one truly exists. Kandinsky, for instance, used specific colors to evoke their corresponding emotions. He painted with shades of blue to spark spiritual speculation in his viewers and with yellow to unsettle them.

Understanding the relationship between abstract and synesthetic art is pivotal to understanding and appreciating the art itself and the mental phenomena that occur to create it. Some of us already have a certain level of experience creating or observing and interpreting abstract art, but chances are most of us haven’t explored the synesthetic realm. This is because it never occurred to us that, for example, a certain taste would be unquestionably linked to a certain visual. On the other hand, passionate musical notes and haunting visuals do often send chills down our spines. These “dual-sensory experiences” provide an instant in which we can experience our surroundings and internal responses at a deeper level, building within each of us a sincere, personal connection to art.

In the words of 20th-century abstract painter Mark Rothko, “A painting is not about experience, it is experience.”