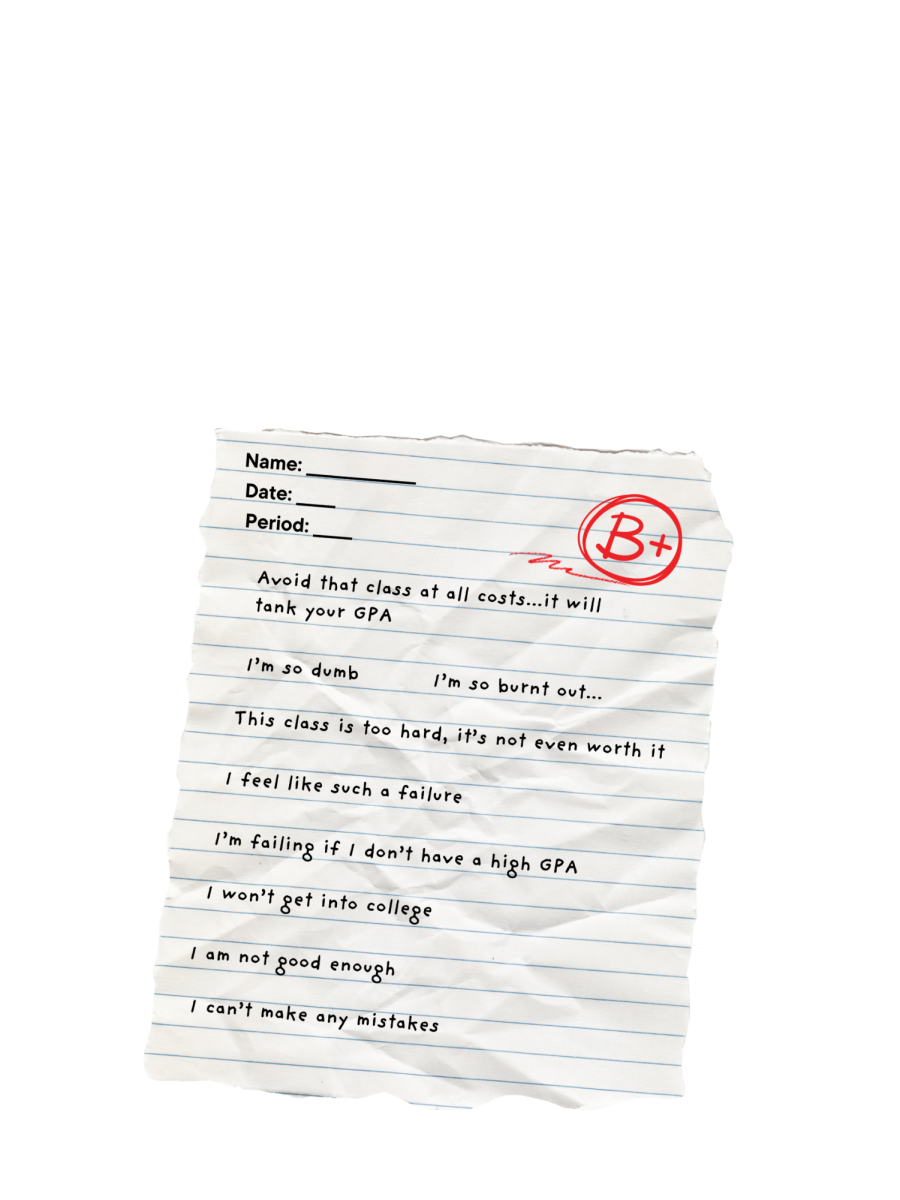

Contrasting the stark white paper, a crimson letter rests mightily in the corner, its edges faintly etched by the stroke of a ballpoint pen–saturated with the heavy psychological weight of either pride or profound failure.

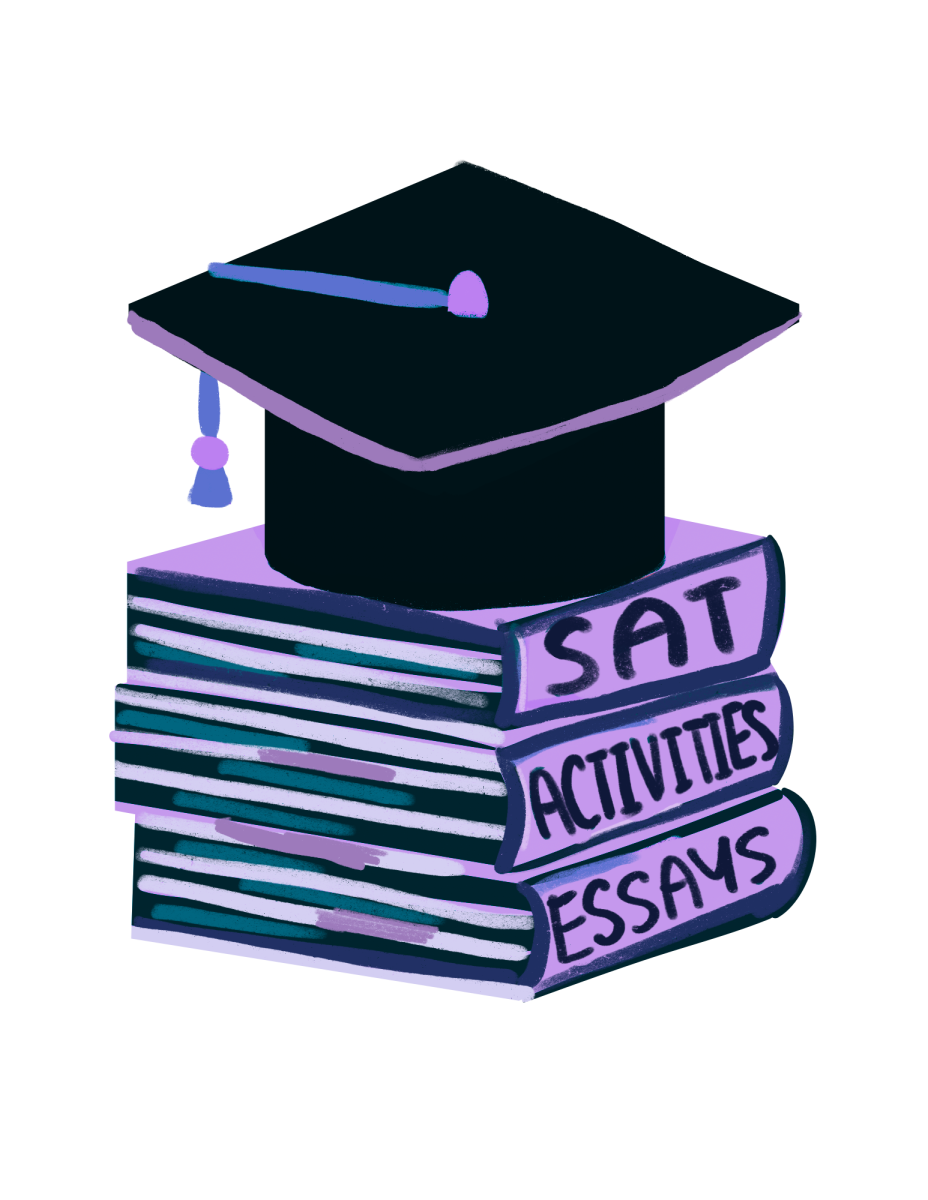

In a world where colleges demand more than academic excellence, students fill their calendars with grueling 12-hour days of rigorous AP courses, endless extracurriculars, and sky-high test scores all to incessantly chase after that 4.0 GPA, as though their future and self-worth hinge solely on the outcomes of these accomplishments.

A 2002 study conducted by the American Psychological Association found that more than 80% of college freshmen define their self-worth based on academic competence over their family support and appearance.

“Students have pressure and voices coming from many directions (parents, counselors, the media) telling them that they have to get good grades “or else…” and the “or else” might involve competing for a scholarship, internship, or summer program,” Math Instructor Meaghen Harris said.

From day one, the reminder to get good grades is a tool to satisfy college admissions officers and employers who merely glance at transcripts; however, beyond the focus of our GPA, are students missing out on what is truly important: real learning?

What if, instead of letting grades define the extent of our understanding, we paused to truly seek knowledge, much like the cliche advice to “stop and smell the roses”?

While admittedly, grades have been a traditional indicator of measuring a student’s understanding of the breadth of material being taught they also “serve as a reflection of how prepared a student is for success in the next level of that given course or subject matter,” Harris said.

Yet, students have intrinsically been more inclined to focus on the rewards of grades, which leaves learning on the back burner.

The fixation on grades is part of the significant issue that originates from our academic motivation.

Intrinsic motivation, also known as motivational orientation, refers to motivation that is “self-drive in a positive way,” where a student’s primary focus is on their intrinsic desire to learn, whereas extrinsic motivation depends entirely on external factors, such as praise or specifically our grades, to drive the learning process.

If our emphasis lies in extrinsic motivation, often burnout and an overwhelming obsession over grades, develop that can affect our motivation for learning and how we interpret grades in relation to ourselves.

Within this fixated mindset, students often label themselves as either “A” students, “B” students, or “C” students, which can emanate discontentment when they get failing grades, hindering not only their motivation actually to understand the content but also the beauty of learning.

When the focal points of conversation are built on “That class is a guaranteed A” or “Avoid that class because it will tank your GPA,” the fixation on grades leaves no room for the real purpose of school–learning.

Although it is not possible to downplay the importance of our grades, which floats in the ether, knowledge is where the real power lies.

Instead of pining for grades that are reliant on our performances on certain tasks such as assignments, assessments, and projects, they do not fully reflect the extent of our understanding outside the context of the classroom.

While grades matter at the moment, knowledge is useful beyond the scope of a test and instead can continuously be built on and serve us for the rest of our lives no matter the profession.

Instead of memorizing mundane equations or niche vocabulary words for an exam, spending the time to understand the material and asking “why” is valuable in real-world settings when an interviewer does not have your transcript in hand.

“The classroom experience and our teachers promote understanding, but I think the grading system intrinsically only encourages memorization. Often times I feel like I am studying just to get through a test, and after that test is over and that stress is gone, so is that content.”

By the same token, when we only study for grades, every subject can feel like a chore that stifles our own intellectual curiosity, like robotically ticking the boxes of requirements we need to graduate.

However, when we focus on knowledge and learning and take classes we find enjoyable, we can discover diverse interests that excite us and utilize these skills in the future.

In prioritizing learning for the sake of knowledge, we can discover new passions and classes instead of just burdening ourselves with striving for that “A.”

Grades, which serve as a snapshot of our understanding, do not fully capture the ongoing growth we experience through learning.

While achieving good grades may coincide with knowing the material, learning itself is a lifelong habit that is cultivated well beyond high school and college.

If we focus on understanding rather than just grades, we can build a mindset that promotes ongoing growth rather than letting bad grades dissuade us from wanting to learn further by challenging ourselves.

In a culture where failing can equate to weakness and grades are stringent, learning is valuable when building resilience, problem-solving, and perseverance–skills that are integral in the future and mirror the real world.

When we detach our self-worth to a grade in the corner of a piece of paper, we can expose ourselves to the joy of learning that is not determined by categorizing our intelligence by failure or success.

So, how can we shift our mindset to foster intrinsic motivation rather than relying on extrinsic rewards?

First, setting up meaningful goals that resonate and align with our passions makes learning more meaningful.

Rather than just achieving a grade, if we set up bit-size goals, we can pursue mastery while learning instead of solely focusing on the outcome.

While getting good grades might seem like the end-all-be-all at the moment, it should not define our academic journey; instead, we should turn it into a tool that can guide our curiosity and love for learning.

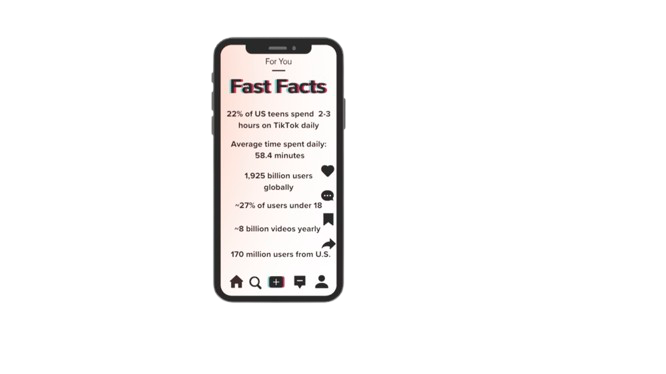

Students continue to endure long hours of studying from dusk till dawn, buried under piles of homework.

“At the core, I really love to learn and try to put a greater emphasis on understanding the material,” Comis said.

“However, I am at the stage in my high school career where I have to start thinking seriously about what I do to get into college, meaning that my grades have become extremely important. There is so much pressure to be “perfect” so that you can get into the “perfect” school that at times I lose track of why I really love to learn,” Comis said.

So, the next time you want to learn about, non-Newtonian fluids, the Dancing Plague of 1518, or the Fermi Paradox, stop and smell the flowers.