Political Advertising Reaches Santa Barbara County

October 14, 2022

In the 2022 midterm elections, political advertising has already broken records. Even in California, a deeply-liberal state with few competitive races, political advertising spending has almost reached an eye-watering $500 million. In contrast to past election cycles, voters are more likely to to see political ads on their devices, not just on television, as digital advertising has grown rapidly.

Laguna students have been exposed to a wide variety of political messaging across the internet on platforms like Instagram and Facebook, Hulu’s connected TV advertising, Snapchat, and most crucially, Google.

Google is the biggest platform for reaching voters because Google allows political spenders to buy three different categories of advertising.

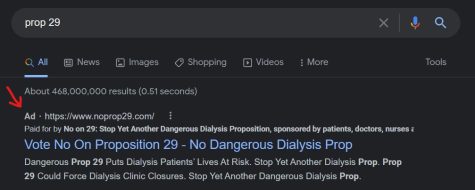

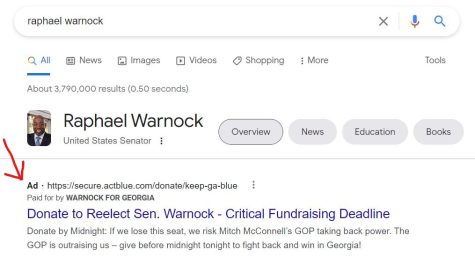

First, using Google Search, political campaigns and PACs can spend to advertise on search results. Typically, these search placements focus on persuasion, the process of using advertising to vote for you or vote against your opponent. These ads can be positive, highlighting a success or the candidate’s website, or can be negative, providing a link to a website that attacks a candidate connected to the search.

Here’s an example of a positive and negative Google Search Ad:

Other political ads include Youtube video advertising, which can include 15 second or 30 second placements. With Youtube’s userbase including hundreds of millions of American voters, it’s become a staple for political advertising. Youtube ads are the most similar to traditional television ads, and often, it’s the same video used on TV. The third is Google Ads, a broad database where political advertisers can spend for GIF-based or image based advertising on the web’s millions of websites. These can be used to target voters based on their district.

———————————————————————————–

Within Santa Barbara’s congressional district, $264,000 has been spent on political advertising on Google alone, a massive total for Santa Barbara and San Louis Obispo considering both counties are in safe Democratic districts.

What’s the spending coming from? Let’s take a look at the biggest advertisers and the ads:

1. “Yes on Prop 27”

Spending on Google Ads in Santa Barbara: $99.5k

About the advertiser: “Yes on 27” is the gambling corporation-funded ballot committee (a political action committee that solely can fundraise and spend in support or opposition of a proposition) campaigning for Proposition 27 which would legalize online gambling.

Some of the “Yes on 27” advertisements focus on small Native American tribes that don’t own casinos, arguing that the proposition would help fund their communities.

Other ads argue that the Proposition’s proposed regulations on gambling, including a 10% tax, would help fund affordable housing and combat homelessness.

2. “Yes on Prop 26, No on 27” + “Californians for Tribal Sovereignty”

Spending on Google Ads in Santa Barbara: $83k

About the advertiser: Opposing Proposition 27 is the majority of California’s Native American tribes, using two committees “Yes on 26, No on 27” and “Californians for Tribal Sovereignty” to argue against the proposition. The committees are also funding a rival ballot measure that would legalize online gambling, but would keep tribes in control.

“No on 27” ads highlight that most tribes oppose Prop 27, presumably trying to negate Prop 27’s ads focusing on their smaller tribal support.

Other ads from “Yes on 26, No on 27” accuse Prop 27 of endangering children by legalizing accessible online betting. Interestingly, this ad highlighted a mother who opposes the proposition, but only targeted male voters over the age of 35.

3. “No on Prop 29″

Spending on Google Ads in Santa Barbara: $30k

About the advertiser: California voters are facing another dialysis ballot measure, Proposition 29, which would increase regulations on dialysis clinics and require clinics to keep a licensed medical professional onsite. Funded by the healthcare union SEIU United Healthcare Workers West, supporters aren’t pouring money into expensive advertising. Instead, political observers see SEIU UHW as trying to exhaust the dialysis industry by forcing them into spending big on election campaigning. Inevitably, the dialysis industry is spending big to defeat the measure.

“No on 29” advertising focuses on the possibility that the increased regulations could cause some dialysis clinics to close, endangering patients.

4. Senate Candidates from Georgia and Pennsylvania? (Raphael Warnock and John Fetterman)

Spending on Google Ads in Santa Barbara: $6k

About the advertiser: Democrats have a lot of small-dollar donors. What’s that? Big-name candidates have millions of supporters that give in small increments: $2, $15, $27. Individually, it’s not enough, but these campaigns have millions of donors, and it adds up quick. Candidates now are more likely to use digital advertising to reach supporter and fundraise than to use it for persuasion. For instance, incumbent Democratic Senator Reverend Raphael Warnock is using Google’s ad exchange to reach his supporters with a donation ask focusing on his seat’s importance for Senate control.

Other candidates and national democratic groups are spending with similar appeals.

5. Local Candidates: “Gregg Hart for Assembly”

Spending on Google Ads in Santa Barbara: $2k

About the advertiser: Ironically, local candidates spend the least on political advertising targeted at the Central Coast. However, it makes sense when considering how political campaigns are run: at scale. Local candidates, like the Democratic candidate for the State Assembly, Gregg Hart, often don’t have considerable funding for a digital advertising budget. Most of their fundraising goes into mailings, canvassing, and television ads. However, Hart’s campaign seems to understand Youtube ads are effective at reaching people that don’t have cable TV.

His main Youtube ad focuses on his experience on the Santa Barbara County Board of Supervisors and his endorsements from “nurses, firefighters, and teachers.”

Data and advertising examples sourced from Google’s Political Advertising Database.