Locked Up

December 6, 2018

I grew up going to zoos and aquariums. Both teach children about animals and provide an experience you can’t find in books or television.

That’s why I found it so odd when I saw movies like “Blackfish” or “The Cove” coming out. I didn’t understand why people would boycott such wonderful places: don’t they care about the animals When I got older, I figured it out: they made those films because they care about animals. And I do too, but at the time I was simply too uninformed to see what was right in front of my eyes. I’ve debated for a long time about whether I should write about the Santa Barbara Zoo, considering that it’s a touchy subject. Opened in 1963, the Zoo is one of our small city’s best features. With the ocean nearby, mountains towering above and the beautiful animals on display, the Zoo is hard not to love. As I got older and more involved in the well-being of animals, I became vegan and started advocating for their rights. I took a nostalgic trip to the Zoo with my young cousins, ready to show them the happy animals and relish in the smiling faces the kids would soon have. When I arrived, it couldn’t have been more different.

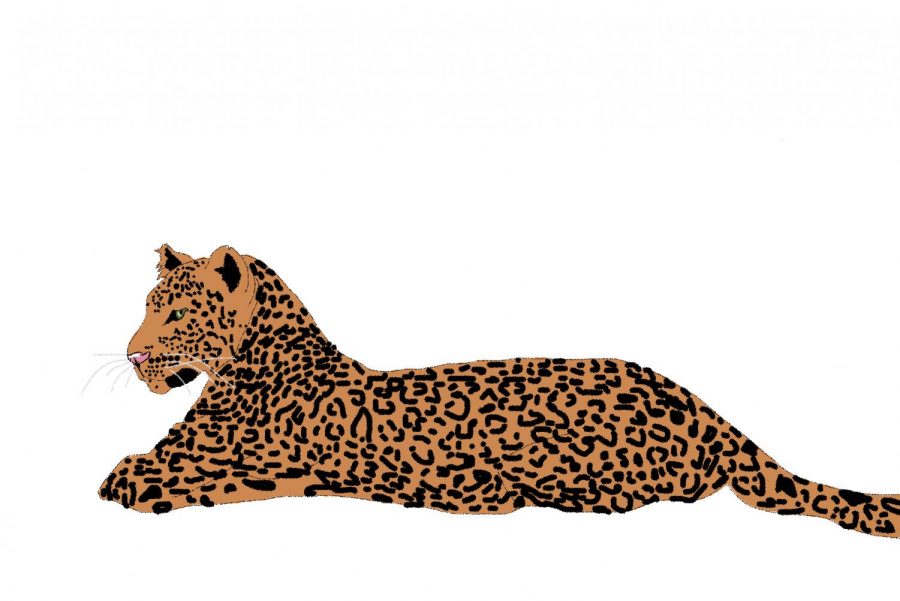

When people are younger, they look at everything through a filter of innocent perfection. I strolled past the inadequate cages and the stifling perimeters set up to contain these animals, and I grew unhappy. I watched as the lions paced, the gorillas ate their feces, the snow leopards shielded themselves behind rocks to avoid the relentless staring and the elephants swayed all day long. I couldn’t cower any longer–– tell- ing my friends and family about my hatred towards zoos but not making any change. For the first time in years, I head- ed back to the Santa Barbara Zoo to get a fresh perspective of the animals in captivity. When people ask me why I hate zoos so much, the first thing that comes to mind is the animals’ well being. Although our local zoo is far better for the animals than some others, that doesn’t excuse it from being a zoo. It is like saying one prison is nicer than another. It is still a prison, no matter how nice it is. If you browse the Zoo’s website, you may notice how they like to boast about their expansive 30 acres and the 500 animals on site. While this sounds impressive, I thought it seemed a little too good.

I delved into what they actually mean by 30 acres. This includes the vast parking lot, retail stores and food places. I watched kids sledding down grassy hills, getting their faces painted, riding a mini train around the park and eating ice cream. To me, this doesn’t sound like you’re describing a “conservation” center: it seems like a commercialized amusement park. Not to mention the many play structures for the kids. For a major tourist and resident destination like this, it is understandable that they would need a parking lot that size, but it came at the cost of enough room for the animals. On their website, the Zoo claims that the animals “are exhibited in open, naturalistic habitats,” which I found laughable because of how small and unstimulating their environments are. What seems “open” about an enclosed cage? How can a concrete enclosure be natural? I don’t see the slightest logical reasoning behind this. The snow leopards belong in the frozen Himalayan mountains, hence the name. That’s why, when I spotted the leopard resting in the far corner of the enclosure in sunny Santa Barbara. I felt an aching pity for these animals who were once wild and free and have now degraded to serve as eye candy for the Zoo equivalent of window shoppers. A snow leopard in California? The Zoo’s website states that “On the rare occasions that the temperature rises above 85 degrees, they run the sprinklers, freeze the cats’ food, and provide special icy treats.” No matter whether the animals can withstand a temperature, I want them to be where they are most comfortable: their natural habitat. The mammals are often seen pacing, plucking hairs, regurgitating and ingesting. It is not a rare occurrence, in fact, it is so common there is an official word for it; zoochosis, psychosis caused by confinement. These behaviors almost never occur in the wild because of how active and stimulated they naturally are. Being well fed, sheltered from predators, the weather, and provided places to sleep, there is nothing for them to strive for. Nothing that fuels them with the spirited will to survive. It takes away their very nature. As well as boasting about their acreage, the Zoo boasts about their enrichment programs. Zookeepers make many of the animals go through this under the notion that it “provides them with activity.” Trainers have the Asian elephants paint canvases for their daily dose of artificial stimulation. However, in many Asian countries, specifically Thailand in Elephant Trekking camps, elephants are tortured, beaten and trained to paint pictures for entertainment. Knowing this, I recoil when I watch videos of the animals “having fun” and doing their splatter painting on a canvas while the crowd applauds. It is obviously not in an animal’s instinct to make a spectacle of themselves in such an unnatural environment. So why do so many of us support these programs that keep animals and train them to think their sole purpose in life is to be on show for humans? That nothing other than that will define them? The Zoo, when describing the Afri- can Lion on their website, said, “He willingly comes over to the training wall to work with the keepers.”When you think of a wild predatory mammal in the vast plains of Africa, standing at the beck and call of a bunch of humans in need for entertainment likely doesn’t come to mind. Humans and wild creatures don’t usually interact, and when they do, it doesn’t go well. Antony Marchiando, a multimedia editor for the Santa Barbara Channels, wrote an opinion column about the inhumane zoos that, “If the habitats are a good size for the animals, they are going to go where they are more comfortable and frankly that is away from people.” The CEO of the Santa Barbara Zoo, Richard Block, responded to the col- umn, “It is not clear if the writer actu- ally visited our zoo. If they had, they may have noticed that the animals appear to be very comfortable in close proximity to people.” I cringed when I read that last line. Was that meant to be positive? Animals desiring to stay close to humans? Because, to me, this signifies that these lions and tigers and bears are no longer true animals. As Block tries to defend his institution, he digs himself into a deeper hole, saying a complete oxymoron, that animals are most comfortable when they are with their predators, humans. As I starting leaving the zoo that day, I saw it as my solemn duty to complete the “full experience,” and I went to see the main attraction. This was what I dreaded the most –– the captive elephants. I watched with sorrow as they were fed greens. A young boy, eight at most, was admiring the elephants. With an ice cream in hand, he leaned over the railing and asked his dad, “Why does such a big elephant have such a small home?” I saw as the dad struggled to answer the question and ultimately ignore it, distracting his son by talking about how cute the elephants looked. I was shocked. A five-year-old boy knew some- thing was off. He didn’t know what was so horrible about what he was looking at, but I could tell he didn’t like it. I realized then that within our young generation in this equally young century, we will have the power to change what past generations have called the norm: captive animals. I can say with certainty that there will be a time in the future when zoos will be extinct. It may not be soon, but I believe that we will find a way to respect our fellow animals and let animals and humans coexist in harmony.