Cat Calls

From the Perspective of a 17-year-old Girl

April 27, 2017

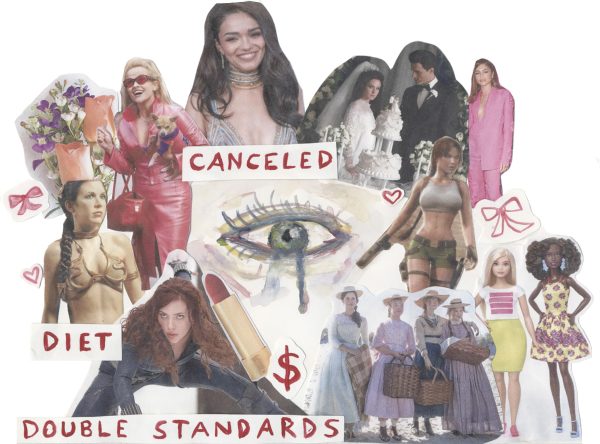

It may seem paradoxical, but receiving compliments from strangers on the street lowers my self confidence significantly. Unlike some women who view catcalls as complimentary ego boosts — for example, New York Post journalist Doree Lewak, who wrote the infamous “Hey, Ladies — Catcalls are Flattering! Deal with it” — I find them frightening, objectifying and truly blood boiling.

To the man who followed me, a then 15-year-old girl, on a State Street side-street continuously asking, “Are you a cheerleader?”: I am not, nor have I ever been a cheerleader, although my bare legs in shorts on an 80-degree August morning led you to believe it was reasonable to inquire. It was not reasonable to inquire, and your comments left me feeling sick to my stomach for the rest of the day.

“I resent the notion that it is okay to make someone feel like a sexual object,” said Head of Upper School, Lolli Lucas. And catcalls are exactly that — a condoned method by which men are able to dehumanize women of all ages.

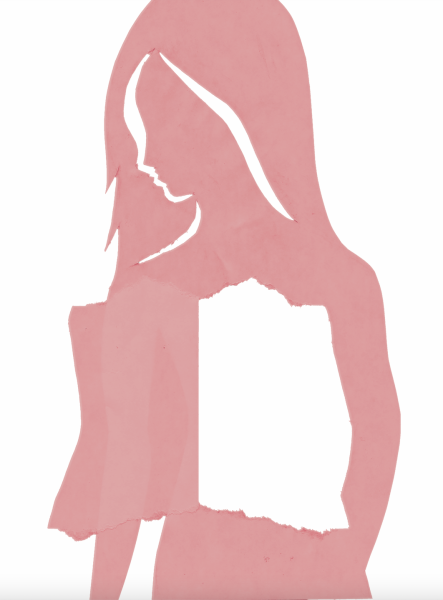

After balancing chemical equilibriums in AP Chemistry and analyzing and implementing historical documents into long essays in AP United States History, one objectifying comment from a middle-aged man on the street makes me, a high school girl, feel like my worth is no more than my body — like my intellect, hard-work, wit and compassion are meaningless.

So it is because of this that I find catcalls so unnerving. I have never been physically harassed by a stranger on the street, (excluding the one time I got punched in the face by a drunk woman in Italy while eating gelato, but that’s another story) and to be honest, although my heartbeat does speed up when catcalled, a large part of me knows that on a public street in broad daylight, it is unlikely a catcaller would get physical. But the fact that men can, at any time, equate my self worth to my sexuality, infuriates me.

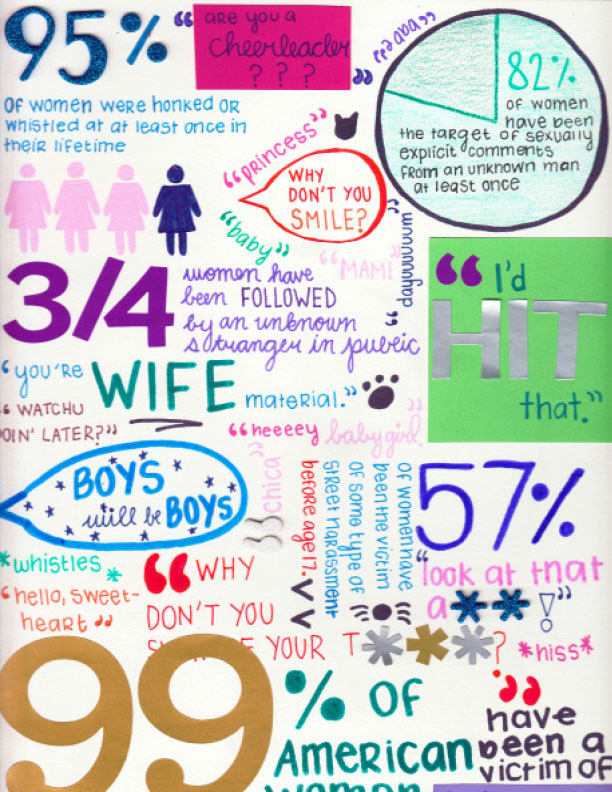

Christine Sisto, an editorial associate for the National Review wrote in an article titled, “No, Catcalling is Definitely not Flattery” that “According to a report by Stop Street Harassment, 65 percent of women have experienced ‘at least one type’ of street harassment in their lifetimes.

57 percent of those women say they have been harassed before age 17… (How does that make you feel, dads?) 57 percent of all women have experienced verbal harassment, and 41 percent of all women have experienced physically aggressive forms of street harassment. That’s a lot of ‘compliments.’”

Sisto goes on to explain that these ‘compliments’ are really opportunities for a catcaller to achieve power.

This ego boost that comes with identifying a woman as an object should no longer be accepted. The commonly acknowledged get-out-of-jail-free card that ‘men will be men’ and ‘boys will be boys,’ needs to be eliminated.

After hearing strong negative opinions on catcalling from high school girls, I went on to see if this trend continued when asking high school boys their perspectives on the same topic.

However, no matter how hard I searched, I initially could not find a highschool boy who condemned catcalling. Many brushed it off as something they had no knowledge of or something that “doesn’t seem like that big of a deal.” Some boys even said they do it themselves, as “just something my friends and I do as a joke.”

I started to lose hope until I spoke to junior Javier Abrego, who said about catcalling, “I’ve never witnessed it, but if you have the audacity to objectify women and shout disrespectful things at women, you should get some help.”

Following my interview with Javier, I spoke to sophomore Oliver Heyer and junior Sasha Hsu, who both had similar responses to Javier’s.

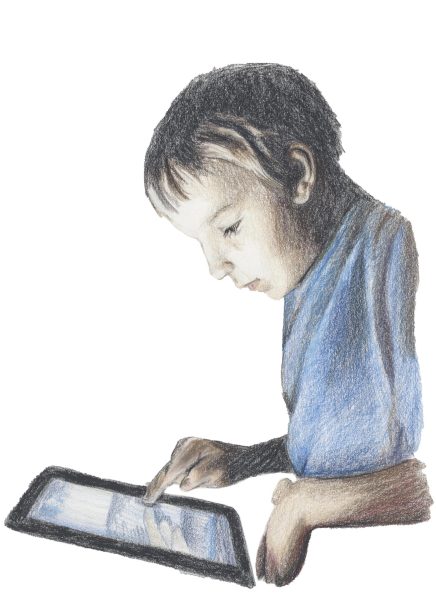

From speaking with teachers and students and researching online, I realized that the catcalling culture will only be stopped if we teach our sons and daughters how to treat people, before we teach them how to react to the ways others treat us.

No matter how many women come together to speak out, nothing will change, because catcallers get their power through the reactions of their victims. This is why, instead of focusing on telling our daughters how to react to catcalls or how to perceive catcalls as flattering, we need to focus on teaching our sons that it is not okay to seek power through the intimidation and objectification of women. Only then will this underlying allowance of derogatory behavior be eradicated, allowing women to feel more like equal human beings than window-shop merchandise.

In the comments section of an article I read, in which a female Harvard University student, Lily Calcagnini, addressed “The Insidious Problem of Catcalling,” I spotted a comment from an anonymous user, which I found to be particularly distasteful. On catcalling, the user rebuted: “It is unpleasant, but it is a compliment even if unpleasant and unwanted. Cheer up– in 20 years or less you will be invisible.”

To the anonymous author of this comment, I say that in 20 years or less, neither the female author of the article who attends one of the top universities in the country, nor I will in any way be invisible.

In 20 years or less, I will be making a difference in whichever field I find to be my passion, pushing myself to create change and influence and inspire others. Although I will not look as youthful, and therefore stereotypically attractive, as the comment implies, I will most certainly not be an anonymous, anti-feminist internet troll, because you, @‘63, are invisible.